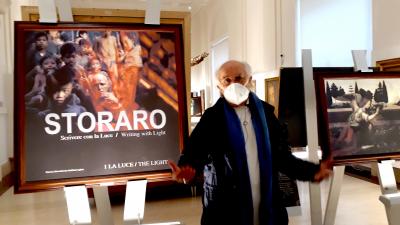

The magical lens of cinematographer Vittorio Storaro

ROME – The exhibition, “Scrivere con la Luce” (Writing with Light) currently running at Palazzo Merulana, Rome, gives an intimate and exclusive insight into the intuition and the techniques of triple Oscar winner cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, who set his imprint on some of the most significant films of the 20th century, including Coppola's “Apocalypse Now” and Bertolucci's “Last Tango in Paris” and “The Last Emperor.”

Spread over three floors of Palazzo Merulana, the former abandoned Rome Health and Vaccinations office, taken over and transformed into the present cultural hub by entrepreneur and art collector Claudio Cerasi and his wife Elena, the exhibition unfolds like a visual biography in a progressive sequence covering fifty years of the maestro's career and documents his progressive use of the double exposure techniques which became his hallmark.

Storaro documents his sources of inspiration, which came from celebrated works of art, with reproductions of masterpieces by Caravaggio, Bacon, Rousseau, Carpaccio, Magritte, Leonardo, Dejeneka, Botticelli, Covili and others set up alongside the still images from the relevant films. Some are reasonably obvious, like Carpaccio's “St. George and the Dragon” with “Lady Hawke” and Francis Bacon's “March Triptych” which seems to mirror the plot of “Last Tango in Paris.” Others are more obscure.

Born in Rome in 1940, Storaro initially studied at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia (the Italian Film Institute) in Rome, graduating in 1960. The breakthrough came eight years later, with Franco Rossi's “Giovinezza Giovinezza” (“Youth March”) where his revolutionary use of chiaroscuro won him the Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists Nastro d'Argento award for the best black and white photography.

“I discovered Caravaggio by chance,” he recounts. “In a visit to the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi. His use of light to underline the revelation of truth in the “Vocation of St. Matthew” made a profound impression on me. At that point I realised that I had been taught technique - but not art!”

This was the beginning of a lifetime study devoted to the language of image, crystallized in three books devoted to light, colours and the elements – disciplines that characterize three phases in his life: “A Journey with Light,” “Chromatic Emotion” and the “Equilibrium of the Elements,” grouped under the collective title of “Writing with Light.”

“The title is inspired by the word “Photograph.” This name comes from two Greek words: “Phos,” meaning “Light” and “Graphé” writing.”

A chronological sequence of photographs from some of the most celebrated films he worked on takes us to “The Conformist” (1970), a political drama set in the Fascist era based on the novel by Alberto Moravia. Bernardo Bertolucci had been struck by the young cinematographer's use of light and shade in “Youth March” and invited him to collaborate. In this movie, Storaro introduced his theories on the physiology of colours and human reactions associated with different wavelengths of light, enclosing the main character in contrasting light and shade to underline his psychological dilemma. A version of the 15th century painting of “The Battle of San Romano” by Paolo Uccello hangs nearby.

“I admire this painting because it was revolutionary for its time. All the other artists of that era were painting Madonnas and saints so this was something really new and unconventional. The artist was a true visionary.”

“The Conformist” led to “Apocalypse Now,” arguably the most revolutionary film of last century.

“When Francis Ford Coppola got in touch with me about the film I told him I didn't want to do it. I said I didn't do films about war. It wasn't my type of thing. But he sent me this book - Joseph Conrad's “Heart of Darkness.” He told me to read it along with the film script. The book was a revelation. It is all about the brutality and horror of the European colonization in Belgium Congo and the suppression of the local culture by the invaders and I realised then what he wanted to achieve.”

“Apocalypse Now,” in fact, is powerfully anti-war. The famous scene where the helicopters bomb the Vietnamese village just after a class of children have come out of school was calculated to shock the conscience of the American people. When the film came out it was initially boycotted in the United States because of its anti-military theme.”

The film subsequently won the Palme D'Or at the 1979 Cannes Film festival and also gave Storaro his first Academy Award. Today it is considered a milestone in the history of cinema.

Rousseau's “The Snake Charmer,” he adds, was the inspiration for the surreal world of dark shadows and the menacing jungle atmosphere he created in the film.

Bertolucci's “Last Tango in Paris,” had come out four years earlier. Another history-making film, the sex scenes caused immense scandal at the time. This was the first film where Storaro gave full rein to his studies on the symbolism of space and colour, panning the camera over the empty walls of the apartment where the lovers meet and portraying Brando in filters of reds and orange to represent the fact that he has entered the sunset of his life.”

The role of the science of colours became more and more important in Warren Beatty's “Reds” (Storaro's second Oscar award) and in “Dick Tracey”, where he used the primary colours to reproduce the comic strip origins of the story. Dick Tracey (the Hero) is seen in yellow, the colour of the sun, while dark blue and indigo are used for the gangsters and villains and violet for the killers.

In “The Last Emperor” (1986-87), which won him his third Academy Award, the colours were subtly modified to reflect the progressive ages of the emperor.

“Colours convey visual emotions to the audience in the same way that words convey sensations in literature and notes in music. I don't want to ever accidentally misuse a colour and give the audience the wrong information.”

From the study of the dynamics of colours, Storaro moved on to the third phase: the study of the four elements: fire, water, earth and air. “The Equilibrium of the Elements” centres round the natural elements of life and finds their expression in “Lady Hawke”(1983), where the lovers are forced by fate to live in two different time slots, and “Little Buddha” (1993) which deals with the cycle of rebirth, as well as in the last ten films of his career as cinematographer.

He is now working on his second trilogy in the “Writing with Light” series, with three books: “The Muses,” (already published), “Visionaries” and “Prophets” to be completed shortly.

“They deal with the phenomenon of creative intuition, as symbolized by the Muses. The ten Muses of the Greeks governed inspiration in the fields of poetry, history, dance, music, comedy and tragedy. My tenth Muse is dedicated to imagination and, like the Cinema, she feeds on her nine sisters.”

cc