Books: Avoiding bullets, battles, bottles and bankruptcy

ROME - Once, walking along the Gloucester Road, my habitually elegantly-dressed father was accosted by a bloke, who had stumbled into the cold out of The Zetland Arms, with the words, “Got a light, mate?” Pausing only to wink conspiratorially at me, my father fished his solid-gold Dunhill lighter out of his pocket, cupped it between his hands against the winter wind and, as the man approached, drew the lighter, it’s sputtering flame, and the man’s face toward him; until they were virtually nose to nose. “Yes,” said my father, in his still-thick Polish accent, “I do have a light. But I am not your mate!”

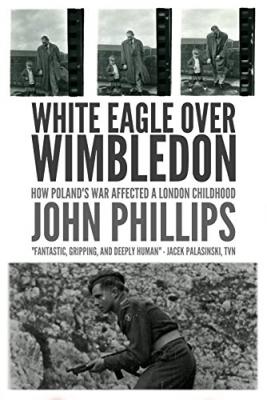

John Phillips’ admirable book White Eagle over Wimbledon is chock full of similar anecdotes which bear witness to our Polish countrymen’s seeming inability to resist deflating other people’s egos, even when the result could be the inevitable deflation of their own. Phillips himself, as he mentions in the book, has picked journalistic fights with some formidable enemies. As we speak, litigation over one such continues. Where his father fled both Nazism and Communism yet, ironically and sadly, was badly treated finally by Thatcherite Britain, Phillips benefited from a privileged childhood and education, but has used his education and journalistic skills to criticise, quite rightly, any regime of any political colour which has practised inhumanity to its citizens, and also to take the fight to press barons and governments which attempt to hinder the freedom of the press.

This noble, or impolitic, depending on how you look at, refusal to kowtow to the powers that be seems to be hard-wired into Polish genes, much as it seems to be a part of the hard-drinking journalist mentality. Insane levels of courage, bravery and sheer bloody-mindedness are required of these men who have repeatedly thrown themselves into the front lines of conflicts in Beirut, Baghdad, Belgrade and elsewhere. It has been my privilege to meet several such on my travels and all have been complete gentlemen, with that characteristic modesty that is the sign of true greatness. Speaking of his father’s bravery during the Warsaw Rising and in the non-Communist Resistance, Phillips admits at one point in the book, “I believed there was a fund of courage in my genes into which I could tap.”

The book is littered with details about the casualties of this genetic curse, as well as shining examples of this genetic blessing. This is Phillips theme to which he returns with many examples and copious historical and personal illustrations. At one point he quotes a Polish pilot who maintained that learning merely to survive during the war made the trivial conflicts of office or career later seem trivial and not worth bothering with. I have felt this throughout my life, without ever having seen combat. The author’s experience, fighting illegal dismissal by Murdoch’s ruthless News International, shows that this is not necessarily the case. Forced to fight for his family’s survival, to continue the education of his beloved daughters, Phillips has to battle, borrow and connive until he and the BUJ can bring about justice for himself and his impoverished family.

Phillips is full of praise, and rightly so, for the educational system that nourished his sensibilities, mine and our contemporaries. Free at point of delivery during the 1960s and 1970s, English education’s basic decency, humanity and clarity created a legacy in the humanities, arts and journalism that is, tragically, being undermined daily. The book is full of learning, the leavening of omnivorous reading, and humour. The sketches of Uncle Jan, his schoolfriends, the portraits and anecdotes about other larger than-life journalists, about the late Father Gula, the amusing quotations from Rebecca West and many others, all serve to bring the book vividly to life and make it memorable. It is an intensely readable book. Brought up, partly In Kensington and Chelsea, I moved among these people, meeting girlfriends in Daquise and eating with my father in both Ognisko and the exclusive Polish Air Forcce Club, the latter sadly now gone.

My father, like the author, adored Italy, visiting every year. I often felt he would have been happier there than in England. It’s Catholicism, and the great friendship he nurtured there, curiously with an Italian communist professor, were two things he deeply valued. My father was bemused by the apparent coldness of the English. “I’ve lived in England for forty years, Adam, and I don’t have a single English friend.” May it not just be that there is a spiritual or humanitarian impulse in Poles (like other great and noble peoples) that is never satisfied by or even interested in mere financial success?

Phillips’ book in this sense forms a sort of an Odyssey in reverse, the hero attempting to avoid the sirens and rocks of bullets, battles, bottles and bankruptcy. A story that will be identified with by many. A child of mixed stock can feel that he or she does not fit in with the society of either their mother or their father. “Where do I belong? Will ever reach home?” How will I know I have arrived there?

Three million Polish Jews and three million Polish civilians and military personnel, 18 percent of the population, were systematically slaughtered by the Germans. Polish suffering has been underplayed by history and Poles accused of collaboration. My own father, caught trying to escape the Russians was handed back to them by the Nazis and thrown at the age of 18 into a Siberian labour camp, later in 1941 making his way to Persia to join General Anders Polish 2nd Corps and fight in Italy at Monte Cassino.

John Phillips' book is a successful attempt to try to right the balance, to look, now a lot of post-war and Cold War dust has settled, at how this brave generation of Poles made their way into English society and how successfully they were assimilated. How another generation of Polish immigration may have influenced Brexit. Nevertheless, as our personal dramas play out, often governed by impulses we still do not fully understand, or which we have not mastered, I am sure that, irrespective of understanding our past, or making peace with it, the solution to all our problems is how we live today, and the decisions we make daily: this shapes our future.

Adam Czarnowski was educated at Christ's Hospital and University College London. A poet, writer, artist (with work in the Tate Modern) and photographer (www.adamczarnowski.com), he lives on Paros in the Cyclades.

White Eagle over Wimbledon. How Poland’s War affected a London Childhood.

By John Phillips

Endeavour Media. On sale for 10,99 euros at the Almost Corner, Anglo-American Bookshops in Rome, or Amazon, Abe.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/White-Eagle-over-Wimbledon-childhood/dp/1527210626

if