Umbria: Forgotten treasures... revealed by the earthquake

PRECI, UMBRIA - The 2016 earthquake that devastated a swathe of Central Italy has focussed attention on one of Umbria's lesser known treasure.

The village of Preci, tucked away in the folds of the Sibillini Mountains National Park, is surprisingly little known. Surrounded by more celebrated neighbours like Norcia, the birthplace of St. Benedict, patron saint of Europe, Cascia with the Sanctuary of Santa Rita, the saint of the roses, the spectacular lentil fields of Castelluccia, the Festival town of Spoleto and the Marche regional border, Preci was often passed over by visitors and pilgrims following the ancient routes and trails of St. Francis of Assisi. Perched on a hillside, the little town, however, immediately set itself apart with its immaculate historic centre clustered around the lofty clock tower of Santa Maria della Pietà and its grand pastel-coloured town houses, the prestigious residences of one-time wealthy citizens. Its unassuming air of gentile affluence distinguished it from the rough hewn stone-built homes of typical Umbrian villages.

The secret of the unusual prosperity displayed by this remote community lay in the Castoriana Valley below, site of the Abbey of Sant'Eutizio. The Abbey was first founded in the 5th century by immigrant Syrian monks seeking a peaceful haven, who brought with them the ancient medical knowledge of the Levant and Middle East. The Benedictines, who later took over the Abbey, preserved and expanded their unique healing arts, both with traditional herbal remedies but also through surgical practices virtually unknown in Europe at the time. When the Consiglio Lateranese of 1215 banned the brothers from practices involving “cutting and blood letting”, the monks passed on their knowledge to the local population, composed mainly at that time by pig farmers.

“They learned quickly,” I was told. “Because human anatomy is similar to a pig's.”

They must have learned well because soon the farmers transformed themselves into respected and successful doctors, subsequently creating a lineage of 30 elite families of Preci surgeons who continued to practise their skills, which they passed on from father to son, for the next five centuries.

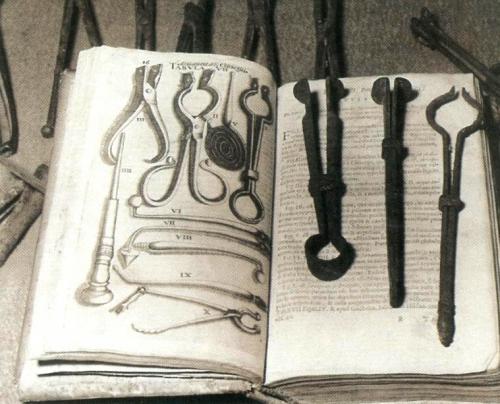

Prior to the fatal 2016 earthquake that devastated a swathe of central Italy, it was possible to visit the small but well-documented Museum of Surgery tucked under the town hall, as well as the Abbey's collection of historic surgical instruments and documents relating to the town's unique and amazing history.

The Preci surgeons became world famous and their skills were requested by all the ruling houses of Europe, who were prepared to reward them handsomely for their services. Preci surgeons dealt with an impressive variety of complaints, ranging from hernias, polyps, kidney and gall stones, as well as hare lips, blocked tear ducts and urinary tracts. They also performed castrations, usually at the request of parents who wished their young boys to retain their soprano voices, much in demand since Pope Sixtus V imposed a ban on women singing in church choirs. Part of their success appears to lie in the fact that they seemed to have appreciated the importance of sterilizing their instruments in order to prevent infection – a principal cause of post-operation deaths for hundreds of years.

Durante Scacchi (born 1540) who belonged to one of the leading families, was celebrated for his invention of a cauterizing technique that limited haemorrhaging, and was also known for his ability to remove eye cataracts and prevent blindness. This required special skills, as well as nerves of steel and a steady hand. He described his technique in 1596 in a celebrated medical treatise entitled “Subsistium Medicinae” copies of which still exist and have been hailed as “one of the most fascinating and influential books on surgery in the history of medical science”.

Durante Scacchi used golden needles, considered less liable to carry infection. He operated almost instantaneously with alternate hands. Seated in front of his patient, whose head was held steady by his assistant, he inserted the needle in his right hand into the patient's left eyeball to remove the cloudy film that had formed over the lens. Almost simultaneously, he performed the same operation on the right eye with his left hand.

One of his most famous patients was the “Virgin Queen”, Queen Elisabeth I of England, whose operation is documented in a letter written in 1590 by his younger brother Cesare. It was Cesare Scacchi who actually carried out the operation as at the time Durante was occupied at the papal court. The 55 year-old Queen's eye surgery was a complete success and Cesare was richly rewarded with a thousand gold scudi and many other rich gifts.

The prestige and fame of the Preci School of Surgeons lasted into the 18th century when modern medical techniques began to take over and the skills of the remote Umbria school of surgeons were gradually forgotten. Unfortunately, the 2016 earthquake has swept away the Museum of Surgery along with the Sant'Eutizio Abbey. The exhibits that it was possible to save are at present carefully preserved in the Deposito Per I Beni Culturali di Santo Chiodo (a special repository reserved exclusively for endangered works of art) at the Santo Chiodo site five kms from Spoleto, along with over 7000 paintings, crucifixes, sculptures, altar pieces, ex-votos, church bells, candelabra and various objets d'art recovered from the damaged churches and museums of the earthquake zone. The Santo Chiodo depot was first created after the 1997 Assisi earthquake but subsequently it has proved inadequate to house the enormous number of artistic treasures displaced by the more recent earth tremors of 2016. A new storage unit has been built next door and another, funded by the Umbtia regional administration, is programmed to be created nearby.

On certain days, the deposit is open to the public for guided tours and visitors can have a fascinating glimpse into the work of the dedicated team of restorers who patiently clean, piece together and reinforce damaged objects returning them, as near as possible, to their former state of glory. Eventually, whenever possible, all will be returned to their place of origin.

A recent success story, hailed as “a miracle,” was achieved with the 15th century crucifix, painted by Nicola di Ulisse da Siena, that hung suspended above the main altar of Sant'Eutizio. It had reached the specialized Vatican restoration laboratory in some 30 fragments. Patiently pieced together, the restored crucifix was recently exhibited in the Vatican Museum “Fragments of Hope” exhibition. Preci too can celebrate the recovery of a well-loved icon - the so-called “Vesperbilt”, or “Vesper Image” a particularly moving stucco and wooden representation of the Pietà, believed to be of Germanic origin, that was one of the treasures belonging to the Romanesque Church of Santa Maria della Pietà. In addition, restoration work after the 1997 earthquake revealed forgotten gems that had been concealed under the plastered over counter-facade – a series of frescoes dating from the 14th - 15th centuries which have now been returned to the light.

TO-DAY:

After the 2016 earthquake, with its epicentre in nearby Accumoli and Norcia, Preci's historic centre was devastated. For almost eight years, it was virtually a ghost town. Much of the village had been declared unsafe and the 724 residents who were living there at the time of the catastrophe moved out, many to provisional housing set up nearby. The town's administrative centre, with its Council Chamber and the nearby Bell Tower were destroyed, along with the Museum of Surgery and the historic archives.

However, the people of the mountain areas are resilient, with a strong sense of community and local identity. Most of them are determined to return eventually to their former homes and the Italian authorities are committed to restoring what has been damaged or lost.

Work has been slow to start, partly because of the many difficulties involved, such as the prior need to analyse the terrain and fault lines, cumbersome Italian bureaucratic procedures, delays in funding and the difficulties of installing anti-seismic technological solutions on both existing and new buildings in order to safeguard them for the future,

In Preci itself, priority has been given to rehousing the original inhabitants and to the reconstruction of communal buildings. The fear of depopulation is one shared by all the local authorities of the mountain areas, as expressed in the August 24th 2024 “Report on Post-Earthquake Reconstruction in Umbria” that states: “the efforts made have not concentrated exclusively on the physical reconstruction of the places affected by the 2016 earthquake but also on the rebuilding of social and economic institutions and businesses in order to encourage re-population and the revitalization of the areas involved.”

The task is daunting, involving not only rebuilding homes, historic churches, monuments and public buildings, but also roads, communal and sports facilities, hospitals, public transport and energy networks.

The historic Abbey of Sant'Eutizio presents special problems. A fine example of an early medieval fortified monastic building, it had changed little since it was reconstructed in the 14th century after a previous catastrophic earthquake in 1328. Built onto a rock face that was shattered by the violent 2016 series of earth tremors, much of the building collapsed along with it, reducing the facade, the bell tower and apse to rubble. The contract for the Special Programme of Reconstruction Work for Sant'Eutizio was signed in October 2022 and efforts to recover the apse were underway before the end of that year. It will be a long haul before the splendid Abbey and the Town of Surgeons return to their original form but determination, know-how and optimism are not lacking.

ms

© COPYRIGHT ITALIAN INSIDER

UNAUTHORISED REPRODUCTION FORBIDDEN