Umbria's 'Rosetta Stone' open door to a mysterious past

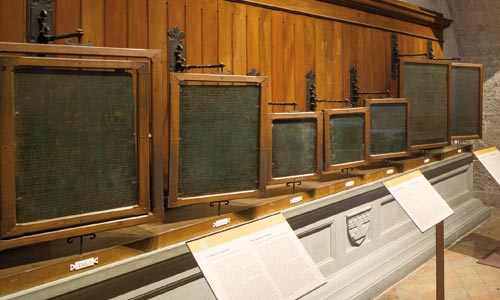

GUBBIO -- One of Italy’s many unsung treasures, the inscribed bronze tablets of Gubbio give a rare and fascinating glimpse into the forgotten world of the pre-Roman civilization of central Italy. The extraordinary Eugubine Tablets hang on the wall of a room in the Palazzo dei Consoli, an imposing 14th century edifice facing onto the Piazza Grande of Gubbio in Umbria. Inexplicably,they are little known and do not feature on the “must” list of the average tourist on the track of the masterpieces of art for which the Umbria region is famous.

And yet, the seven bronze tablets, dating between the 5 th and 1st century BC caused a sensation when they were first discovered in the ruins of the Roman theatre of Jupiter in 1444. With admirable foresight, the Gubbio town council bought them, describing them in the purchase act as having “different letters, both Latin and mysterious ones.” But some five centuries were to go by before these “mysterious” inscriptions were finally and fully deciphered.

The Eugubine Tablets (also known as the Iguvine Tavole) are engraved on both sides in two languages: one in early Latin and the other in the lost language spoken by the Umbrians, a prehistoric people who inhabited central Italy, from the Apennine mountain area and the Tiber Valley to the Adriatic coast before the Roman conquest. Just as the more celebrated Rosetta Stone allowed experts to unlock the key to the language of Ancient Egypt, the Eugubian tablets opened the door to a mysterious past, allowing experts to penetrate the secrets of a language dating back to the Bronze Age, and thus acquiring a wealth of insight into the sacred rituals, laws and legal practises carried out for centuries before the birth of Christ.

The Rosetta Stone, which dates back to 196 BC, was discovered in 1799 at Rashid (Rosetta) by French soldiers during the Napoleonic campaign and is one of the most prized and visited

exhibits in the British Museum, London. One of its three inscriptions was in Ancient Greek which allowed experts to crack both the Demotic script and the sacred hieroglyphic script used by the

Ancient Egyptians. The text contains a somewhat banal decree celebrating the anniversary of the coronation of the Pharaoh Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The bronze plaques of Gubbio, on the other hand, describe in minute detail the sacred rituals and customs of a long lost civilization whose origins are lost in the mists of time. The tablets contain the description of religious practices that were carried over some five centuries by a union of city states led by the central city of Iguvium (the present Gubbio). The plaques were created at different periods and their measurements vary. For convenience, they have been numbered from I to VII, with III and IV believed to be the oldest.

Altogether the tablets contain 4,365 words inscribed on 12 sides The oldest texts are in Umbrian, using the Etruscan alphabet, while later inscriptions use Latin characters. This caused much initial confusion and the task of deciphering them was further complicated by the fact that some of the inscriptions read from right to left while others are written from left to right. The Umbri were an Italic people subjugated by the Romans between the 4 th -2 nd centuries BC. They were legendary even in Roman times, when they were considered to be the most ancient people of the Italian peninsula and survivors of the Great Flood. Previously the sacred texts would have been preserved on other, less elaborate materials, like parchment, cloth or wood and experts believe that the recurring threat of Roman invasion compelled the Umbrians to document their beliefs and customs in this more durable metallic form.

The Tablets demonstrate that the Umbrians, far from being a primitive tribal people, lived in a highly organized society that, for many aspects, established the basis of what we see as modern civilization. Tables II and V record the ritual of the Patto della Decade, (Pact of the Ten) referring to the local confederation of 10 city-states (which later became twenty) linked by an alliance that governed trade agreements, tributes and taxes, as well as common beliefs and religious practices. The relationship with the gods was governed by rigid rituals aimed at obtaining and keeping their favour and guaranteeing the prosperity and wellbeing of the community. These rituals were presided over by a 100-member Confraternity called the Atiedian Brethren, (named after the mother city of Atiedio, now Attiggio near Fabriano) under the supervision of a High Priest, who was usually, but not always, appointed from among their ranks. Interestingly, this personage could be called to order if he failed to follow the exact ritual formulas or achieve the required results. Tablet V states that the Confraternity also decided the fine he had to pay for an unsatisfactory stewardship.

The Holy Trinity of the Ancient Umbrians consisted of Giove Grabovio (the Father), Marte Grabovio (god of the shepherd warriors) and Vofione Grabovio, god of fertility who guaranteed the community’s future. Sacrifices were an essential part of the ceremonies to win the gods’ favour and centred round the immolation of a specific animal – generally sheep, lambs, pigs, goats and cattle but sometimes, around harvest, dogs or puppies were offered on the altar (a custom carried on also by the early Romans). On the administrative side, the Tables also set out the tributes to be paid to the central state, as well as the regulations regarding commerce and exchange among the member cities, withdistinction made between private and public property.

The Umbri appear to have been basically a peaceful and civilized people, much disturbed by troublesome neighbours, like the aggressive Romans and raiding pirates from the Adriatic. The warrior class was an elite made up of Atiedia citizens, who seemed mainly concerned with defence rather than conquest. Table V contains the lyrical Imprecatio, an invocation to the god or goddess Torsa Giovia (unlike the Greeks, the Umbrian divinities did not take on human form) in which divine intervention was requested to scare off the enemy and force him to turn his attention elsewhere.

The number three had a special significance, cropping up in various forms in all the rites and sacrifices and many modern researchers believe that a trace of the ancient customs have survived to the present day in the form of the yearly Feast of the Ceri, three gigantic wooden structures, each 5m tall and weighing 300 kgs, that are paraded through the streets of Gubbio in honour of three Christian saints, Ubaldo the Protector of the city and of builders, St. George, protector of the merchants (represented, however, as an armed horseman) and St. Antonio, the guardian of farmers. There are other, even more significant signs that the ancient memories of the Umbrians continued to smoulder over the ages, even after they were assimilated into the Roman empire. Mount Ingino, the Holy Mount of Giove Grabovio, was duly taken over in the early Christian era, dedicated to the 12 th century Bishop-Saint Ubaldo and subsequently immortalized by Dante as “the Mount of the Blessed Ubaldo.” And even today, it has preserved its special spiritual allure. Every Christmas, it transforms itself into a gigantic fir tree, outlined by over 400 fairy lights stretching 75 metres up towards the summit and visible for miles around, making it one of Umbria’s unmissable festive season highlights.

For further information: www.unicaumbria.it/storia-e-storie-autori/Fioravanti -Federico/

© COPYRIGHT ITALIAN INSIDER

UNAUTHORISED REPRODUCTION FORBIDDEN