A hitch-hiker's guide to Sarajevo's deadly galaxy

SARAJEVO-- The sickening crack from a Serbian sharpshooter's rifle made my American colleague jump bolt upright in the driver's seat. "Take it easy," his young woman Bosnian interpreter said with a gentle smile as the car hurtled down Sniper’s Alley toward the Holiday Inn hotel's underground garage. The high velocity bullet ricocheted with an eery, loud echo across the otherwise deserted highway.

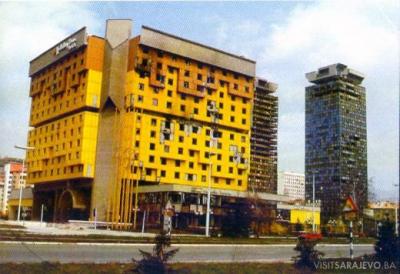

As Bosnians remember the siege of Sarajevo that began 20 years ago, it is curious to recall how journalists from Rupert Murdoch's empire had to hitch-hike around the city. News International decided it couldn't afford to buy an armoured Land Rover. Soon after arriving at Sarajevo airport on a French military plane to report for The Times in 1993, I jumped into a soft-topped jeep driven by a television crew heading into town. Colleagues at AFP's busy office in the shell-pocked Holiday Inn took pity on me. I joined their American reporter on his daily rounds to count bodies in the city morgue. I supposed he drove a French automobile.

"We don't use crap cars," he told me, "we've got a Mitsubishi." Next day I cadged a ride in CNN's armoured car to a news conference at the television centre. The "armour" used to plate journalists' vehicles in the Balkans was dubious protection against heavy weapons. It was reassuring, however, to feel cocooned safely against the small arms fire taking a daily toll of civilians.

Heading out to the beleaguered front-line suburb of Dobrinja, I begged a lift from Leandro, an Italian reporter from Il Messaggero. His Bosnian driver's battered Volkswagen Golf careened past makeshift concrete barriers set up alongside roads to protect pedestrians from the snipers in the hills ringing the city.

For ordinary Sarajevans, any motor vehicle was luxury compared to surviving on foot. At his easel in Dobrinja’s Akademski Slikar art school, Nedzad Kapich, aged 16, tried to ignore the sound of the shooting in the street outside as he sketched under the watchful eye of Mihrizan Mimica, his teacher. "Every day for seven months I have run past snipers through three checkpoints to reach my drawing class," Nezdad told me. "I really hope the situation improves. There are 22 graves by my building and those are just people killed in my street."

Best-prepared was the camera crew of RAI Italian state television. RAI's president lent them his armour-plated Alfa Romeo, a relic from when he was a target for Red Brigades terrorists. As they sped through the town of Gorni Vakuf a Muslim gunman obligingly tested the armour with a burst of AK 47 fire. “It worked,” the RAI correspondent told me with a grin in the Holiday Inn coffee shop.

Upstairs I borrowed the Reuter office satellite phone to file my dispatch to London. Correspondent Kurt Schork was busily sending reports of the fierce fighting under way outside. My daily newspaper told me to leave Sarajevo. On the airport road we were caught in cross fire between Serb militiamen and Bosnian forces. Fortunately I was in a French Foreign Legion Armoured Personnel Carrier. A Bosnian soldier and I pulled closed the overhead hatch as we were showered with grenades and the black legionnaires cursed "putain, putain."

At the airport the terminal came under mortar fire, killing two Foreign Legionnaires on patrol on the runway. My flight was cancelled and I had to return to Sarajevo for another night, hitching another ride down Sniper’s Alley with a New Zealand photographer wearing a desert camouflage helmet who had taken pictures of the death of the legionnaires for Paris Match. The next day I left Sarajevo for Split but the civilians stayed.

As newspaper reporters, however, we at least had the luxury of sending stories only once a day. News agency journalists such as Kurt Schork for Reuters, which did invest in an armoured vehicle for its staff, faced a deadline every minute.

As Mr Murdoch spends hundreds of millions to compensate celebrities whose phones have been hacked by his reporters, the decision by the then Times editor, Peter Stothard, to save a few thousand pounds in Sarajevo on an armoured car seems, with hindsight, questionable.

No matter how good his equipment, however, no war correspondent is immune when death touches him on the shoulder. Kurt survived the siege. He was shot and killed four years later while on assignment in Sierra Leone.