Is the next Nobel Laureate this 30 year old Nigerian maverick?

LAGOS - Writers who write and inhabit the world of post-colonial Africa tend to face myriad of challenges. I do not mean the problem of finding quality publishing platforms or sparse readership in a sea of millions. This challenge is a little more subtle, but no less problematic. It is the problem of having to live and navigate life in a defective democracy and waking to the decay or near decay of various state institutions.

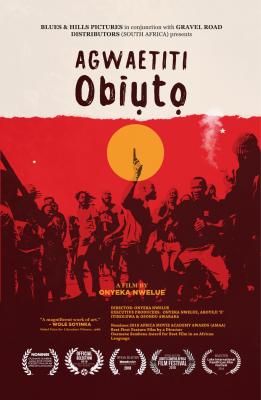

Against this background, there is that ever present possibility that the writer’s work and his politics would intersect. Onyeka Nwelue, currently a Research Fellow at the Ohio University in Athens, embodies this conundrum, and some may be right to suggest that a writer’s work and his politics shouldn’t be mutually exclusive. At 30, and with nine published books to his credit, including a debut novel that won the TM Aluko Prize for First Book and Ibrahim Tahrir Prize for Fiction, Onyeka, a filmmaker, is a man that should not be ignored.

We are at a bar in Maboneng, Johannesburg, three miles from the University of Johannesburg, where he had just been appointed as a Visiting Lecturer to teach the works of Flora Nwapa and Feminism at the Department of English. “I wanted to remind the world of this awesome woman whom everyone seemed to have forgotten,” he tells me. “How she lived. So fiercely independent. Unafraid of being an outlier. And how much she embodied the feminist values that have become a mainstay in the neoliberal politics of identity.”

Highly opinionated, sometimes to the point of annoyance, Onyeka tells me how much this has been both a gift and a curse, and why he has found his art the best way to live his truth. “I have been called a loud mouth and a talkative. I have no problem with it. In fact, to prove that I’m not just a loud mouth, I’ve been spurred to go on and get things done. Clearly, his controversial second book, Hip Hop is Only for Children which won the Creative Non-Fiction Book of the Year at the 2015 Nigerian Writers’ Awards confirms this. It rattled a handful of Nigerian top musicians who were chided, if not ridiculed for mediocre stage performances and vacuous content. He however developed a knack, it would appear, to channel that fiery tongue into other channels of expression. It was then that filmmaking began to gain ascendance in his creative orbit. “I got tired of asking why no one was discussing Flora Nwapa when her first book was nearing 50 years of its publication, so I went out and did a documentary on her. I screened it at Ohio University, and they asked me to join them as a Visiting Lecturer.” The documentary not only turned out highly acclaimed, but was one of the finalists to the African Movie Academy Award, Africa’s biggest award for filmmakers.

Various academic scholars have discussed the feminist undertones of Flora Nwapa, Africa’s first published female novelist, but much of that discussion happened outside the day to day gaze of the Africa. In creating that documentary, Onyeka brought the discussion to the doorstep of the common person, showing how she lived, and how her works mirrored the aspirational tensions of her life, her independence, and while she might have spoken so little about espousing feminism as an ideology, she nevertheless navigated life and career in ways that embodied that ideal.

In what was his next visit to Nigeria following his appointment at Ohio University, the writer got into a tragic situation with a police patrol team in Abuja, Nigeria’s Capital. It was close to midnight, as he made his way into the entrance of the hotel where he was staying, but found a woman who was sprawled on the ground, dragged by policemen. “She was literally on the floor, and held my leg, saying I shouldn’t let them take her away.” The gun-wielding security task force unit charged with the responsibility of clearing prostitutes from the streets. “I felt prostitution is not illegal in Nigeria. And quite frankly, if it was a man they saw standing on that same spot at night, they’d not arrest them. There was no telling what they wanted to do to her that night. So I thought I should help.” When he consistently insisted on the woman’s release, he was pounced on and brutally assaulted, that by the end of it, he had several bruises, a bleeding eye, and broken cornea.

Yet, a bigger trying moment would arrive for the writer a day after the release of his second novel, The Beginning of Everything Colourful. The car he was in was rammed into by a Tundra Truck, causing him to be flown out to South Africa where he would spend the next three months in a wheelchair. “I was wheeled out of the hospital in Abuja to go and bring money, else they won’t treat me,” he recalled. “And then when I returned, there was power outage when the X-Ray was being conducted. They sent me a text message five days later that my X-Ray result was out. I was already five days into receiving treatment in South Africa. So from the beginning, I knew I stood no chance of recovery in Nigeria’s public healthcare system and had to leave immediately.”

It was a predicament that nearly blighted the 30 year old’s life, which had remained rich with adventure, controversy, as well as daring cultural productions. He told me shortly afterwards that he suddenly felt an urge to write voraciously two years ago. And when I looked back on the works he produced within that period, it seemed he had imbibed some of VS Naipul’s energy. The Lagos Cuban Jazz Club (Origami Books, 2017), The Beginning of Everything Colourful (Paressia Publishers, 2017), 84 Delicious Bottles of Wine for Wole Soyinka (editor: Origami Books, 2018), Island of Happiness (Hattus Books, 2018) Evening Coffee with Arundhati Roy (editor: Hattus Books, 2018), The Spice Bazaar (Hattus Books, 2018) and A Country of Extraordinary Ghosts (Hattus Books, 2018) were all books spectacularly churned out within a period of two years. He wrote like a man who perhaps felt the palpability of his own ending. Someone who did not want to spend his final moments regretting all the things he did not write about.

In 2004, he was a 16 year old on a night bus, travelling from Owerri to Lagos. It was 900 kilometres risk-laden trip considering the less than palatable security situation in Nigeria. But he had planned to see the Nobel Laureate, Wole Soyinka. That night, he had nothing but the cloth behind his back, and smoking pen. “Nothing could’ve stopped me from going to see Wole Soyinka on that day. I read from the papers that he was to be at the National Theatre Lagos the following day, and I felt that was the only opportunity I may ever get to meet him.”

That would become the start of his relationship with the man, which had long mutated from mentor-mentee relations to that of a father and son. At the age of 18, he went off to India. “Curiosity led me there,” he says, “India was one of the places I had visited many times through books.” But living in the slums of Indiaopened a myriad of vistas into his mind and made him thirst for a bigger bite of the world. He had tasted one diverse culture, and would continue to want more. It was no surprise that following his winning the Prince Claus Grant, he would spend an entire year visiting more than half the Capital cities of Europe, culminating in the publication of his first poetry collection, Burnt.

During this period also, he went on separate tours with Asa, Nneka and Seun Kuti (son to the Afro Beat legend, Fela Kuti), three of Nigeria’s biggest musical exports. On the Euro Tour with Fela Kuti’s son, he mentioned, was where he was inspired to write his third book, Hip Hop is Only for Children, a vehement critique of commercial music which dominated Nigerian air waves, but deeply lacking in aesthetic substance. Some of the Nigeria artiste whom were hurt by details in the publication, which called out for singing trashing songs and brandishing non-existent wealth on social media sent him threatening messages.

He recalls this with a smile, and a mild chuckle. “The book was controversial. But it was popular as well. Nigerians love hypocrites. Those who don’t tell them the truth. If you say things the way I say them, you’ll be everybody’s enemy. The government. Your benefactors. Even the people you’re fighting for,” he says, running his left hand over his mammoth beard. He didn’t write the book, he tells me, because he was trying to court enemies; he simply wanted musicians in the country to do better. To respect the craft. “They have to do live performances with a band, the fans deserve that, not having artist miming their songs.”

As an individual and a creative, music appealed deeply to his imagination. “I admired musicians a lot. I tried to record a song once in a studio, and it was woeful. I learnt to admire those who do it well,” he remarked. So he ended up establishing a small record label, La Cave Musik in Paris, and worked with artists. He attended the Prague Film School in 2010 for a different reason. “I always felt film had the capacity to communicate to a much wider section of the society. You know, many people would’ve never known Mario Puzo the writer if the film, Godfather, wasn’t made. So I always strongly felt that films can be a complementary asset to the craft of writing.”

Perhaps, this might explain, once again, some of the motivations behind the The House of Nwapa documentary, which succinctly captured the life of Africa’s first published female writer, Flora Nwapa. The documentary attempted to explore the personality of Nwapa, her creative talent and her fierce independence, though the eyes of her family members, contemporaries, and literary critics both in Nigeria and abroad. Onyeka’s second film, Island of Happiness was an adaption of his sixth published book, published by the same name, and which, incidentally, was set in Oguta, Flora Nwapa’s hometown. The film traces the lives of young men in the oil producing town, who were jobless and lived in sprawling poverty, waiting hopelessly on the benevolence of their rent-seeking local authorities. Amidst uncaring social environment in which the past time is sex and alcohol, they ultimately become angry and murderous too.

“Every time I was in Nigeria, I had hundreds of young people around me telling me I could help their careers. I mean, I was still trying to help myself, but because I could travel oversea, sometimes, on a whim, they believed I could help them. People were buying me those plane tickets. I was still trying to help myself. But I understood that the system had failed them. The Nigerian system had failed all of us. And I tried to use the film to tell that to the world.”

Earlier in May, Nigerian Consulate in Johannesburg, South Africa, pulled out an already agreed public screening of the film in minute. They had called cancel the event having watched the film and called it “political”. While this ruined what would have been a befitting screening event, it somewhat vindicated his reason for making the film. “What’s happening in Oguta cannot be hidden from the world forever,” he says, his face, quite animated. “That place is an urban ghetto, an oil producing community that have had no electricity for 7 years, and no ATM either. Its last hospital was built by the late author, Flora Nwapa, but even that has been left to fall apart.”

In nearly all of Onyeka’s books, superstition, independence, and the troubles of migrations form the major themes. And this, he attributes to the tensions and anxieties of his own life, and which reflects his own interaction with the world.

At a recent lecture at the University of Johannesburg, Wole Soyinka, had sighted him in the crowd and cheekily remarked, “The Nigerian Clerk is here,” with a smile acknowledging his presence. Not many knew that this young cultural entrepreneur was onto his next big project. A documentary on the Nobel Laureate, capturing his life as an intellectual tethered to the clamour for justice and the dignity of the oppressed, through the eyes of those who knew him closely.