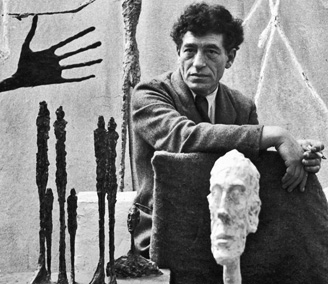

Giacometti at Galleria Borghese

ROME--Only in Rome’s Galleria Borghese could Swiss artist Alberto Giacometti earn his ultimate consecration for having understood the human condition on Earth and rendered it through his art.

His is an art that mesmerises, enchants and encapsulates the evolution of his creative genius with a breadth and depth which lift it to the heights of the masters of classical times.

Thus, he can take up their discourse and let it evolve, from the classical perfection of Greek and Roman times, to the earthly finiteness maimed by the sufferance of post-war years that, itself, stands the test of time.

This exhibition is a dialogue through time, as two perceptions of the human condition enmesh with each other.

The classical style, with the immutable algorithmic shapes of the sculptures and paintings in the permanent collection, finds in Giacometti’s art a natural consequence.

This is fashioned in figurativist, cubist, surrealist, and in the end intimately essentialist terms.

Its lyricism in the later years is found in the extreme conceptualization of the physical dimension, as a last resort flight from the damage wreaked by the world wars and the dehumanisation of death occasioned by them that changed the human condition on Earth forever.

Classical artists could not contemplate this vision, as the idea of a world ravaged by a war fought by tanks and aircraft laden with bombs ready to be dropped, with the unbearable sufferance that it brought about, was beyond their reach.

For the classics, war was above all a matter of prowess, and fundamentally people-oriented.

It was fought by brave men astride prancing horses and armed with bows, spears and shields.

As a result, Giacometti finds leeway to search for the spiritual essence of humanity.

Statues elongate into flimsy, ethereal silhouettes, but with their oversize heavy feet firmly on the ground, crying foul over the modern wars, but yearning for the sky.

Poignantly, Giacometti needs matter merely to convey the ideas that this draws life on. Not the other way around.

His busts meet the beholder through the intensity of the gaze in their eyes, which gives their anatomy a harmony and movement as a result.

Alberto Giacometti was born in 1901 at Borgonovo di Stampa, a hamlet located in one of the Italian-speaking pockets of Grisons, a Canton in the South of Switzerland, and died in 1966 in Chur, its capital city. He lived in Romein 1920-1921. In 1922, he moved to Paris, where he was to stay until his death, except for a period in Geneva throughout World War II.

The conversation in the Galleria Borghese unfolds through 40 artworks, mainly sculptures, but including a few drawings, in 10 separate spaces.

As he matured as a man and an artist, Giacometti believed drawing to be instrumental in gaining a deeper insight into and greater mastery over vision as a process.

This development is apparent in the ‘Portrait of Madina Visconti’, of 1932, in single lines, morphing into the ‘Head of Annette’ (1959) and the ‘Head of Professor Corbetta’ (1962).

These convey his experience of vision, with bundles of lines enticingly beseeching the beholder to embrace the real shapes of the faces, after experiencing the artist’s perception, as they emerge out of nowhere.

A flavour of the depth and breadth of the artist is found in the sculptures in conversation with the ‘Hermaphrodite’ restored by Bernini.

It is elusive, it stirs and evokes frustration, whereas the ‘Spoon Woman’ (1927) brings together the strict formality of cubism and a daring expressive African style that Giacometti had experimented with for a while.

The spoon gives it a marked elusiveness. This is echoed by the surrealist ‘Woman with her throat cut’ (1932) that, barely recognizable as such, with her metamorphosed limbs, in turn, stirs and moves much like the Hermaphrodite himself.

Here, Giacometti takes the human form to its very limit.

And while the ‘Woman walking’ of 1932 in the ‘Egyptian Room’, is a blitz away from surrealism and conveys his full grasp of the classical formalism and rigour inspired by Egyptian sculpture, it is bound to be short-lived.

In fact, this is all lost at the foot of Bernini’s marble ‘Rape of Proserpina’, a timeless eulogy to death.

In it, Pluto snatches Proserpina to the Underworld, bringing immutable earthly values such as beauty and love to an abrupt and dramatic end.

In stark contrast, and replete with historical inevitability, the artist’s torn limbs around it (‘The Hand’, 1947; ‘The Leg’, 1958) cry the pain modern war has caused to humanity, while the ‘Cube’ (1933/34) is deformed to signal a reality that has lost all but its air-tight essence of classicism.

Then, Canova’s sculpture of Paolina Borghese, with her clear-cut anatomical energy and untainted profile, dialogues with the ‘Observing Head’ (1928) and the ‘Lying Woman Who dreams’ (1929) and the deeply personal perceptions of humanity and its condition they embody.

This was aptly encapsulated by Michel Leiris who wrote in ‘Documents’ that some of Giacometti’s artworks are “open air, and the air blown through them shakes nets at the interface between the inside and the outside, sifts corroded by the wind that, surreptitiously, wrap us in moments never experienced before, sending us into a reverie”.

Giacometti’s sculpture broadens its reach even further in conversation with Apollo and Daphne, where the ‘Women of Venice’ (1956) yearn for the heavens, while having their bulky feet firmly on the ground.

And their coarse, almost jagged, skin invites beholders to engage their eyes in a gambolling dance that breathes life into them.

Things are taken to even higher levels of lyricism in Giacometti’s ‘The Walking Man’ (1947), which conveys the mature essentialism that will give him the ultimate entitlement to speak with the classics, with his solemn gait, but fragile, evanescent upward-yearning body emasculated by the war.

Here, the conversation is tight with Bernini’s Aeneas and Anchises, who, towering above, resonate with a dominance of the environment, despite fleeing from a war that heroes had won but other heroes had lost.

And the dialogue goes on between the ‘Staggering Man’ (1950), and Bernini’s David.

The former with its further thrust of the essence of human beings, which is central to their own physical dimension, towards the idealisation of man and his fragility.

The latter, with his classical instant frozen in time with its hauls of shape and energy.

The story becomes more daring in the Loggia di Lanfranco, a spacious sun-lit hall with large windows, where Giacometti’s busts (‘Lothar III, 1965; Bust of Man, 1961; Bust of Annette, 1961) entreat their beholders to perceive their essence through the intensity and acuity of their gaze.

Surprisingly, the dialogue with Bernini’s earthlier busts of Scipio Borghese and Paul V, unfolds on an equal footing, as these too engage the beholder with their intense gaze.

Finally, the giant bronze sculptures, with their remarkable heads, that Giacometti made for the Chase Manhattan Plaza in New York(‘Standing Woman I’, 1960; ‘Tall Woman II’, 1960) take the essence of the woman to entirely new heights, by endowing her with a spiritual richness and divinity demanding reverence.

The ‘Walking Man I’ (1960) in front of them, on the other hand, encapsulates the ultimate essence of humanity, with his unsteady and wary walk through time.

At the end of this journey, aside from the universal message of Giacometti’s sculpture and its distinctive style, the gashed skin and flimsiness of body, gait and posture of his characters and limbs no doubt show his deep bond with his native Bregaglia Valley. This is in parts so narrow and etched in the hard and rough stone that only Giacometti’s lean and flimsy figurines can move freely through it.

Giacometti, la Scultura

Galleria Borghese,

Piazzare Scipione Borghese, 5

Rome

until 25 May, 2014

Tuesdays to Sundays 9.00-19.00; admissions until 17.00

Entrance € 16.00; reduced € 11.50, € 2.00

Booking (compulsory) on 06 32810 or tickets can be purchased at www.tosc.it