Visions of Japan - an insight into the floating world

ROME -- The Rome exhibition “Ukiyoe” (the Floating World) running in Palazzo Braschi Museum of Rome until the 23rd June 2024, highlights the collections of two erudite 19th century Italian collectors who immersed themselves in the what was then the mysterious world of Japan.

Vincenzo Ragusa was born in Palermo in 1841. An idealist, dedicated to the cause of the Risorgimento, he was one of Garibaldi''s “Expedition of the Thousand,” the band of volunteers who landed in Marsala in Sicily in 1860 with the intention of ousting out the Bourbon dynasty of Naples. Ragusa was a sculptor and in 1875 he took part in a competition promulgated by the new Italian government to set up a school of Oriental art in Tokyo. This move was motivated by the desire on Italy's part to secure its presence in Japan, along with the USA and various European countries that had already established their commercial bases in the country. The scheme succeeded because the Japanese government, which had only recently abandoned its long-lasting policy of isolation, was afraid of being overwhelmed by the expansionistic aims of the Western powers and wished to extend its own commercial and cultural influence abroad.

Ragusa was chosen, along with two others – the artist Antonio Fontanesi and architect Gian Vimcenzo Cappelletti. He accepted with enthusiasm as he was keen to explore the special techniques used by Japanese artists. His contract was short – it expired, in fact, in 1882, which was the standard length of contract conceded to foreigners by the Japanese government, but in these few years he made a thorough study of Japanese art and craftsmanship and put together an important collection of Japanese objets d'art which he brought back to Sicily when his contract ended.

He also brought back a wife - the young artist O'Tama Kiyohara, as well as her sister Chiyo, an embroidery specialist, and Chiyo's husband Einosuki, an expert in lacquerwork.

In 1883, with the help of those three Japanese collaborators, he set up a school of Oriental Art in Palermo where Tama ran the female section. Ragusa was keen to experiment Japanese metal working techniques, with view to their application in Europe, and he also wished to promote lacquerware, porcelain and ceramics. However, his enterprise received no hoped-for government funding and Ragusa ran out of money. In 1887 his school was merged with the Reale Scuola Superiore d'Arte Industriale and no longer specialized exclusively in Oriental arts and crafts. A year later, he was forced to sell a large part of his private collection of precious Japanese objets d'art dating from the Edo period, that he had brought back from Japan. Some 1403 items were purchased for a total of 23,000 lire by the Regio Museo Nazionale Preistorico Etnografico Luigi Pigorini of Roma (now the National Prehistoric Ethnographic Luigi Pigorini Museum, which is part of the cultural hub of the Museum of Civilization).

Ragusa's misfortunes continued. In 1898 he was sent away from the school he had founded. For him this was the last blow. He withdrew into private life. In 1916 he sold the rest of his collection of 2769 items to the same museum. However, he never lost his love for Japanese art. In August 1914 he wrote to Luigi Pigorini: “to see (these things) is a delight for the soul, a triumph of art, of the Japanese identity.......”

His wife O'Tama Kiyohana chose to stay in Italy, even after her sister and brother-in-law returned to Japan. In order to marry Ragusa she had been baptised and had changed her name to Eleonora. She was respected and popular and her work was much admired. She seems to have settled well into her new life as she lived for a total 51 years in Sicily and only returned to Japan after her husband's death. In 2020 the city of Palermo held an exhibition about the couple and their work, with special reference to Tama, entitled: “O'Tama – Migration di Stile,” organized by the Federico II Foundation and with the patronage of the Japanese Embassy in Italy.

The honour of holding the most extensive and most valuable collection of Japanese art in Italy, however, belongs to the Museum of Oriental Art in Genoa, thanks to a donation from Edoardo Chiassone (1833-1898), an engraver, who transferred to Japan in 1875 and lived there until his death. He was highly skilled in the art of preparing and designing banknotes and he was noted by a Japanese delegation while he was working for the National Bank of the Kingdom of Italy, developing new techniques to counteract forgery. Chiassone received a commission from the Japanese government to create banknotes for the new currency system that Japan was developing and he travelled to Tokyo in 1875 on an initial classic three-year contact and ended up spending the rest of his life there until his death in 1898. Initially, he was employed directly by the Japanese Ministry of Finance and charged with the task of teaching his techniques to Japanese engravers and printers but he proved so indispensable that his contract was extended indefinitely. Among the important novelties he introduced was the use of watermarks on banknotes for added security. He was so highly considered that he was given the rare privilege of doing the official portrait of the Emperor Mejii and the Empress Shokan, as well as those of several of the most important court officials.

Chiassone never went back to Italy and he is buried in the area reserved for foreigners in the Aoyama Cemetery in Tokyo. However, he donated his lifelong collection of 15,000 items, including prints, musical instruments, weapons, paintings, fans, scrolls, ceramics, rare objets d'art and antiques, to his hometown, Genoa, which set up in his memory, the Museum of Oriental Art in 1905 at the Parco della Villetta di Negro, still its seat today.

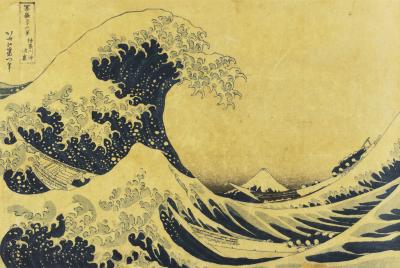

The present exhibition immerses visitors immediately into the colourful and magical world of that long era of peace and stability, known as the Edo period (1603-1868). In 1740 Edo (the original name of present day Tokyo) had become a metropolis with a population of over a million, explained exhibition curator Rossella Menegazzo. The arts and poetry blossomed and the search for beauty, refinement and pleasure became the dominant theme of “Ukiyoe”, the imaginary Floating World of transient luxury and extravagance Once the exclusive reserve of the nobility and the rich, the spread of general prosperity allowed more and more members of the Japanese middle class to participate.

The exhibition takes you under canopies of illustrated scrolls, screens and hangings into galleries of refined paintings of courtesans, actors, musicians, festivals, games, tea houses and crowded street scenes of daily life. Cabinets exhibit selections of the objects collected by Ragusa and Chiassone and a large showcase in the centre of one room displays a magnificent court kimono embroidered in gold thread. Several rooms are dedicated to what is probably the best known form of Japanese art – the depiction of Nature in all its poetical beauty. The introduction of European products such as indaco blue to replace the costly lapis lazuli, and the concepts of prospective, hitherto unknown in Japanese art, reveal the important influence of European art in many of the most celebrated woodcut prints.

In turn, the introduction of Japanese pictorial art had an enormous influence on the European Impressionist movement, and still continues with the widespread popularity of the modern manga cartoon characters and images.

© COPYRIGHT ITALIAN INSIDER

UNAUTHORISED REPRODUCTION FORBIDDEN