Review: Loving Modigliani: The Afterlife of Jeanne Hébuterne

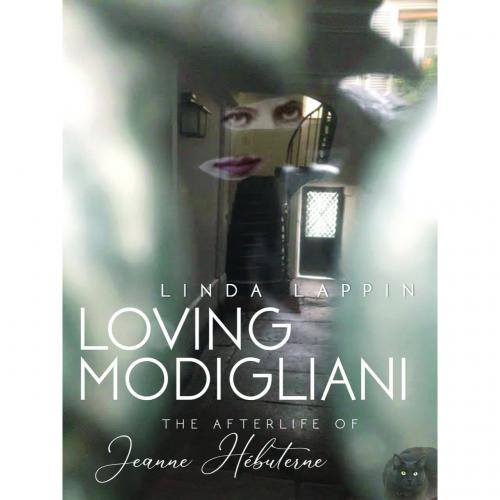

Loving Modigliani: The Afterlife of Jeanne Hébuterne,

Linda Lappin, Serving House Books 2020

The lives of Amedeo Modigliani and Jeanne Hébuterne are irresistibly alluring. Both were artists, both were beautiful and bohemian, and both died tragically and far too young. Modigliani was the classic artiste maudit, his nickname in Paris was Modì, which was a deliberate play on the figure of the tormented artist. Talented, tubercular, iconoclastic, an alcoholic and a drug addict, Modigliani was dying almost from his childhood, but he never let his illness interfere with his art or his loves. He had many, as Linda Lappin’s aptly named novel Loving Modigliani suggests, for he was fatally difficult, charming, and charismatic, and hard not to love.

The last and probably truest of his loves was Jeanne Hébuterne, and Lappin’s novel is an evocative tale that explores her life (and afterlife), her work, and her mysterious legacy. It is a bigger challenge than it may appear--despite the drama and glamour of the post-war, Parisian demimonde that spawned epoch making artists and writers—because there are only a few sketches, self-portraits, and scraps of letters to a friend to illuminate her brief life. Who, in fact, was Jeanne Hébuterne and would she even be of interest to anyone had she not been Modigliani’s partner, a beautiful suicide who could not live without him and ended her life before it truly had a chance to begin? Lappin explores this in her compelling, earlier essay “Missing Person in Montparnasse: The Case of Jeanne Hébuterne,” (2002) and there one can see the beginnings of Lappin’s interest in the fascinating story of a young woman surrounded by the luminaries of Modernism but about whom very little is known. Lappin’s essay is filled with speculation, words like “perhaps” and “might,” suggestions that Jeanne “must have” felt a certain way, or “could have” done or seen something. Because her life is a sort of palimpsest, scrubbed clean and written over by her brother, her daughter with Modigliani, various memoirs from the period, and later work of scholars and art historians, fiction might very well be the best way to explore a life such as Hébuterne’s.

Loving Modigliani is a fascinating story written around a blank, and Lappin builds on the mystery at the same time she gives Hébuterne shape. The novel is at once a ghost story, a love story, a fictional biography, and an academic mystery à la A.S. Byatt. As Lappin cleverly weaves all these threads together, she takes her reader back in time to Paris on the eve of the année folles, through World War II and up to the present, with a few stops in Rome and Venice along the way.

At the center of the plot, whether it is dealing with this life or the next, is the compelling story of Jeanne, an aspiring artist whose fatal love affair with Modigliani altered her life and what we know of her work. Lappin speculates on Hébuterne artistic vision, reimagined through fictional diaries, and how it was influenced by Modigliani but also how it was uniquely her own. As a young woman from a bourgeois family, Hébuterne at first appears tentative and accommodating, which is how she was written about by friends of Modigliani at the time, but Lappin paradoxically fleshes out her character by making her a ghost and the disembodied writer of her own notebooks. Throughout Lappin’s compelling narrative, Jeanne emerges as sincere and kind--she makes great efforts not to alienate her family—as well as determined and daring. For clearly, the traditional portrayal of Jeanne as lacking a will of her own is at odds with her decision to attend art school, to pursue painting rather than design (a bit more respectable for girls of her class than sketching nudes), and to leave the middle-class comfort of her family to live in squalid but thrilling circumstances with the volatile Modigliani. Lappin draws out that willful side of Jeanne, explores her courage and desire to live fully and to become an artist. Alas, there is not enough of Hébuterne’s short life to explore, and Lappin deals with this creatively through a story that traces the effects (ghostly and otherwise) of Hébuterne on several women who follow her: an acquaintance who was there the day Jeanne died and lived into splendid old age, an aspiring art historian researching Modigliani’s fellow painter Manuel Ortiz de Zarate, and finally a curator organizing an exhibition on Modigliani and his circle that included some of Hébuterne’s work. Thus, Lappin takes us on a rollicking ride through the twentieth century with several willful and accomplished female characters, all touched by the short, passionate life of Jeanne Hébuterne and all pursuing the answer to their own mysteries as well as that of Jeanne’s missing works.

Most of us only know Jeanne Hébuterne through Modigliani’s numerous portraits of her. With her swan-like neck and heavy auburn tresses, she stares out at us with clear blue eyes that are curiously blank. It is said that Modigliani drew some of his sitters without pupils because he saw them as inward looking rather than outward looking, and clearly that is how he saw Jeanne Hébuterne. If she had lived past the age of twenty-two, would she have developed into an accomplished painter in her own right, or is her association with Modigliani, a few works, and her suicide her only lasting legacy? Thanks to Lappin’s highly original work that is full of emotion and color, we can puzzle out the artistic clues Hébuterne left behind and contemplate who this elusive figure might have been. Her story, like art itself, haunts us beyond her time and place.

https://www.amazon.com/Loving-Modigliani-Afterlife-Jeanne-Hébuterne-ebook/dp/B08MDCDC9V/

jp-ol-lc