Venice cruise ship ban causes much consternation

VENICE - The Italian government’s declaration that it has overcome years of its own dithering to deal with threats posed by gigantic cruise ships entering Venice’s delicate lagoon represents a step toward resolution but faces resistance from vested interests.

Yet many found the March 25 decree unsatisfying, coming, oddly perhaps, when the pandemic has kept all cruise ships away from the world heritage site. Until 2020 they brought 1.6 million tourists annually on some 700 vessels but caused global outrage by eroding the lagoon, spewing cancer-causing fumes and risking calamitous collisions with monuments.

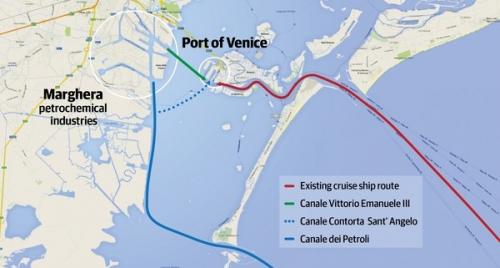

“The decree is not a decision. It is a joke,” said independent city councillor Marco Gasparinetti. It banned cruise ships from passing through the historic centre’s Giudecca Canal, temporarily re-routing them to the adjacent Marghera industrial port, and launched a “competition of ideas” on how to move cruise and some larger shipping to new port facilities outside the lagoon. With Italian governments changing on average every 14 months, the gruppo25Aprile citizens’ campaign spokesman, who favors the Adriatic Sea ports, was sceptical, “Real change? I don’t believe it.”

Speaking for the ruling far-right government of Venice’s mayor, Luigi Brugnaro, councillor for tourism Simone Venturini, echoed Gasparinetti’s view, saying the decree “has nothing concrete… new or definitive.”

Rome had done little about cruise ships since 2012, when the deadly sinking of the Costa Concordia off Tuscany led to banning them from Italian coasts — except in Venice. But now it has put up €2.2 million for the ideas competition. If all goes smoothly, a facility for cruise ships could be ready in a few years.

In pole position is a dock within the lagoon’s Lido opening on the coastline just east of Venice, but the decree also called for ideas for a commercial facility that would accommodate outsized container and transoceanic vessels. That would be a much larger effort, taking a decade or more.

This possibility appeals to Paolo Costa, former Venice port head, mayor and Italian and EU minister, who believes cruising is a non-issue because it will take years to recover from the pandemic. With Italy falling behind its Mediterranean rivals in the shipping race, he envisions an outside port taking advantage of Venice’s strategic location, close to northern European markets, to attract 20-meter draft mega-ships, ones now too big for Port Marghera’s limited 12-meter depth.

Outside ports would also deal with the probability that sea-level rise will one day overwhelm the newly tested MoSE flood gates protecting Venice from acqua alta. Climate scientists predict they may need to be raised so frequently to protect the city that the lagoon port would be virtually cut off.

Outside port proposals have fallen by the wayside before, but this time hopes are raised. In a letter Monday to Italian President Mario Draghi, the Venezia Cambia citizens’ movement called the decree “a strong impulse for finally reaching a solution outside the lagoon,” which two official studies have already recommended.

But the decree also allotted €61 million to prepare Port Marghera for cruise ships until an outside port is built. That “instills concerns that the actual intention is to persist for a long time with cruise ships in the lagoon,” the letter said.

When cruise ships return they will enter via the Malamocco opening, following the Petroleum (Malamocco-Marghera) Canal used by commercial shipping going to Port Marghera. That means they will no longer berth at the Maritime Station docks attached to historic Venice’s west end. Cruise visitors will instead disembark at the industrial port and then cross the Liberty bridge.

Mayor Brugnaro, however, who has long spoken up for tourism and cruise shipping interests, wants to keep using the Maritime Station. He was re-elected last year on a pro-jobs platform mainly by the 200,000 terrafirma voters. He lost the vote of the 80,000 lagoon inhabitants, who wanted sustainable tourism.

Venice has suffered from overtourism due to the rising tide of some 30 million visitors each year until the pandemic left the tourism-dependent city high and dry, with 6,000 job losses and many noted shops and hotels closed.

Venturini, leading plans for a tourism revival by 2022, promises a “better” tourist experience, one controlled by advanced digital monitoring, mandatory booking and fees for day-trippers.

Brugnaro had pushed to reopen the disused Vittorio Emanuele Canal, so cruise vessels could sail from Marghera to the Maritime Station — something lobbied for by the docks’ owners. Re-dredging, however, called “insane and reckless” by lagoon biologist Lorenzo Bonometto, could stir toxins dumped in the lagoon for decades by Marghera industry.

Concerns have also focused on moving cruise ships through the one-lane Canale dei Petroli in competition with commercial shipping, which could snarl traffic to the port, worth €6 billion to the city and employing over 20,000, compared to cruise industry’s 5,000 jobs and €155 million value.

What happens in the years until the outside ports comes on line is critical. The opposition fears that the “temporary” rerouting, could, like the 1933 wooden Academia bridge, end up as a long-term solution.

Brugnaro made his preference for cruise ships staying inside the lagoon clear on TV Sunday, dismissing the outside port: “People will understand in a few years that disembarking tourists from a cruise ship in the sea doesn’t work in any part of the world.”

His comment draws battle lines, but “as long as international attention remains on Venice there little chance that cruise ships will stay in the lagoon,” said economist Giampietro Pizzo of Venezia Cambia. “If the spotlight strays, things will return to business as usual and the little, but strong, local powers will serve their own interests and turn things back.”

nr