Deep state 'invented' in political chaos of post-war Italy

ROME - For Donald Trump the "deep state" is any government official who opposes his actions. For the authors of a book published in Italy this week, it was created by James Angleton and Kim Philby in the political chaos that gripped Italy at the end of World War II.

"The prototype of the 'strategy of tension' was built in the four years from 1944 to 1948 through the creation of networks for clandestine warfare... in which the mafia, freemasonry, and death squads were enrolled," write Giovanni Fasanella and Mario José Cereghino, whose book ‘The Brains Behind the Deep State’ is based on declassified documents from official archives in London and Washington.

The "strategy of tension" was a phrase coined by the Observer to describe the terrorist atrocities of the 1970s that had the effect of propping up unpopular centrist governments dominated by the Christian Democrat party. The authors of the book suggest the seeds of that strategy were sown at the end of the war when communists, fascists, and monarchists were competing for influence and the intelligence services of half a dozen nations were stoking the tensions of a low intensity civil war.

Spheres of interest in post-war Europe had been divided up between the victorious Allies – the Soviet Union, United States, and Britain – in a series of meetings leading up to the Yalta conference in 1945.

Intelligence agencies and their armed proxies sought to advance their cause through violence. A part of the British establishment and its "private" intelligence structures were at the forefront of the competition, Fasanella and Cereghino claim.

"London too was fanning the flames. In the belief that the 'disorder', if governed and not left to chance, would have provided a pretext for a definitive English intervention in the peninsula," the authors write. "Total control of Italy continued to be a fundamental plank of Britain's long-term strategies and of its far from exhausted imperial ambitions."

Some of the diplomats and spies who had cut their teeth in wartime scheming with the Special Operations Executive (SOE) – the secret organisation created by Winston Churchill to set Nazi-occupied Europe on fire – went on to adapt its techniques to the new conditions of the cold war. A 1945 document on the peacetime redeployment of SOE details how it could be used for propaganda, bribery, and sabotage in support of Britain's vital interests. A document drawn up the following year and declassified in 2013 clarified that violent and subversive operations should not be traceable back to Britain.

The clandestine persuasion of reluctant allies in Italy could be achieved by making use of some of the material recovered from the fascist secret police by Federico Umberto D'Amato, a Rome policeman who went on to become one of the most influential figures in the post-war battle against communism.

In November 1944 D'Amato was sent by James Jesus Angleton, the future head of CIA counterintelligence, to negotiate with Guido Leto, the head of Benito Mussolini's secret police, for the handover of many of Ovra's most sensitive files. At the end of the talks in Mussolini's last stand Salò Republic, Leto agreed to deliver 6,000 boxes of files to the Allied military government. The papers were sifted by two British intelligence officers, Major Harris and Captain Baker, before just 167 boxes were consigned to the care of the new Italian government.

It is safe to assume that the material retained in London and Washington gave the Allied intelligence services a powerful hold over members of Italy's political and economic elite who had been complicit with the fascist regime.

Fasanella and Cereghino claim the anti-communist struggle in Italy was financed with mafia drug money from South America, some of it channelled through Milan's Banca Nazionale dell'Agricoltura. The activity was authorised by Count Giovanni Armenise, a director of the bank, who was in regular contact with Captain Philip James Corso, an American counterintelligence officer working for Angleton and suspected of harbouring far right sympathies.

A 1947 intelligence report reveals: "Count Armenise stated recently in private conversation that he was personally financing the armed anti-Communist movement started by Patrissi and Fresa because he thought the time had come to create a movement which could undertake 'street initiatives', which the military movement of the Monarchists could not." Another report on the bank from the same year says anti-communist organisers were seeking financial support "from Italian industrialists emigrating to Argentina because of their Fascist convictions."

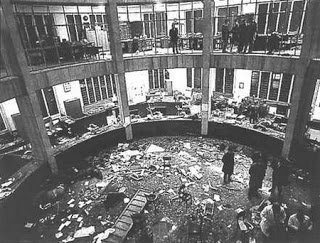

On the afternoon of Friday Dec. 12 1969, a powerful bomb exploded in the lobby of the Banca Nazionale dell'Agricoltura, killing 17 people and injuring 88. It followed a series of more than 200 minor bombings in the course of the year that had caused material damage but few injuries. It set in motion an official cover-up overseen by the Italian police and secret services and unleashed a season of political violence that would continue for two decades.

Some historians suggest part of British intelligence may have been working to head off a military coup – for which the bombing might have provided an excuse – at that time.

Mr Fasanella is less charitable. Angleton and Philby, who also ran agents in Italy at the end of the war and who shared the American's ruthlessness, had set up a prototype of the deep state at a time of acute political tension, he said. "They tested it in Italy and put it into action at a global level."

Mr Fasanella says the skulduggery continued until as late as the 1990s. "The interests, the dynamics, the modus operandi and in many cases even the individuals involved were the same," he said.

Giacomo Pacini, a historian who has specialised in the cold war, said Mr Fasanella's research had widened the examination of Italy's troubled past from the much debated east-west conflict to competition with ostensible allies over energy resources in the Mediterranean.

"He has the merit of looking at Italy's history from a wider perspective. Countries such as Britain and France wanted to block a certain foreign policy that brought Italy into conflict with their own Mediterranean interests," Mr Pacini said.

It may be some time before the classified documents that might back up Mr Fasanella's claims see the light of day.

jp-ppw/jmj