Secret Sounds of the Past

ROME - A five-year project involving ten European universities reveals the lost music of times remote. The surprising results of their research are on exhibit currently in Rome

Did Cave Man have a musical ear? Did the Etruscans entomb their dead to the clink of terracotta rattles? Did Bronze Age children make their own bull roarers? Just how loud was the boom of the Celtic carnyx that frightened the wits out of the invading Roman soldiers?

For the past five years, a group of researchers from ten European universities and conservatories have been working to find answers to questions like these. Focussing on the remains of musical instruments found in tombs and archaeological sites stretching from Sweden to the Mediterranean, a pan-European team of archaeologists, musicians and makers of musical instruments have succeeded in recapturing the long forgotten ghostly music of past millenniums. The results can be seen (and heard) in the exhibition “ArchaeoMusica, the Sounds and Music of Ancient Europe”, in the ex-Cartiere Latina (Paper works) on the Old Appian Way near the San Sebastiano Gate, Rome.

The EMAP (European Music Archaeology Project) was selected from among 80 proposals that were submitted to the Education, Audiovisual and Cultural Executive Agency of the EU in 2012. The five-year research project (2013-2018), financed by the Culture Programme of the European Commission and co-ordinated by the Italian University of Tuscia at Tarquinia, involves specialists from the Universidad de Valladolid (Spain), the Osterreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften (Austria), the Associazione Musik I Syd AB Skane Kronoberg (Sweden), the Deutsches Archaologisches Institut (Germany), the Cyprus Institute (Cyprus) and the University of Huddersfield and the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland (UK).

The “Sounds and Music of Ancient Europe” spans a very long period of time - from the Upper Palaeolithic to the Iron Age and the great classical civilizations. According to researchers, the many varied instruments found in archaeological sites and graves prove that mankind has been making music for at least 50,000 years

Most of the instruments on display were broken or in fragments when they were unearthed and one of the most fascinating aspects of the exhibition is the story of their reconstruction. Many of them were surprisingly sophisticated, requiring very special craft skills and a knowledge of musical sounds. The same materials and methods used to create the originals were adopted to make the replicas, such as a reconstructed iron age kiln to cast the circular Celtiberian trumpet. Visitors can watch videos of the painstaking work undertaken by skilled craftsmen like Scots metalworker John Creed and the French artist Jean Boisserie, creator of the Tour de France cup. Other videos show the first ancient instrument jam session, featuring the Swedish Ensemble Mare Balticum and EMAP member John Kenny, playing the carnyx for the first time after 2000 years.

The exhibition opens with a series of stalactites that were found laid out in a row like the keys of an xylophone, indicating that our most primitive ancestors enjoyed a bit of musical entertainment in the cave home. Nearby, a suspended stone rings like a gong when it is struck with a piece of antler (irresistible for children – and adults)

. The exhibition is divided into three sections, starting from the Stone Age, through to the Roman era and beyond, illustrating how musical instruments – some still in use today – developed. But by far the most fascinating aspect is that researchers have been able to revive and reproduce the notes that these instruments made. A series of multimedial stations allow visitors to hear the sounds of the past that accompanied ritual processions, funerals and war chargers. Thanks to the miracles of Augmented Reality, you can play a virtual lyre, observe 3D reproductions of the instruments from all angles and become immersed in the magic of the Sound Gate that takes you on a sonorous trip to ancient Stonehenge.

The Primeval section, which covers a period from 60,000 BC to 2.500 BC, includes a Neanderthal flute made from a bear's femur, clarinets made of the wing bones of birds or mammoth tusks, rattles with shells or teeth, primitive drums and deer antler scrapers.

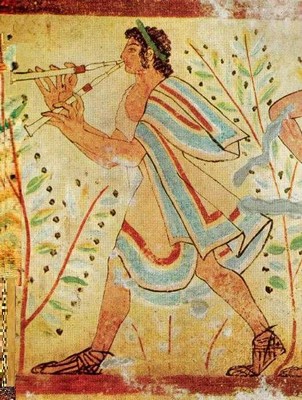

Moving into the Bronze and Iron Ages, we can see some examples of lituus – long-stemmed bronze flutes of Etruscan origin (subsequently adopted by the Romans to sound their cavalry charges), an 800 BC chalcophone (a bronze frame containing rows of metal rings that make a sound like gravel being shaken in a jar) and the double pipes known as the Greek aulos (the Romans called them tibia), made of bone with two protective cases of finely hammered metal. The tone could be adjusted by turning bronze rings inserted between the mouthpiece and the pipe. The aulos is known to have been in use for 3000 years. It features in the wall paintings of Pompeii as well as in the 490 BC Tomb of the Leopard at Tarquinia.

Other intriguing wind instruments include the Greek salpinx (Aristotle compared its sound to the trumpeting of elephants), the circular terracotta trumpets of the Celtiberian tribes of northern Spain, the Roman G-shaped battle horn which curled round the body of the soldier-musician - sometimes spiked to make it into a deadly weapon, and the Iron Age Loughnashade horn from Ireland.

The most spectacular exhibit, however, is the monumental 2 m-long bronze carnyx of Celtic origin, found at Tintignac, France, in 2004. It was buried with seven other examples that had all been ritually silenced with spears thrust down their long shafts. The carnyx was designed to strike terror into the hearts of the enemy. Its bell was in the form of a snarling boar's head with large wing ears – resembling more a dragon than a boar to tell the truth. It is very much in evidence on Trajan's Column in Rome.

The EMAP project also demonstrates just how much ideas travelled, even in remote times. It revealed that the lyre and other string instruments originated in the Mediterranean area but soon found their way to the remote north. The bronze horns, on the contrary, travelled the other way, originating in the Baltic and in Britain during the Bronze Age to subsequently spread south to Etruria and France.

Some traditional instruments are still in use today. The “European Whistle Map” shows a large collection of clay whistles from all over Europe, in all kinds of shapes and colours, that continue to be produced today just like they were 7000 years ago – a demonstration that music continues to cross borders and hold through the ages the same eternal and universal allure.

ArchaeoMusica – the Sounds and Music of Ancient Europe is an itinerant exhibition, which has so far been shown in Sweden, Spain, Slovenia and Tarquinia. It runs in Rome until the 6th December , when it will move onto Germany. Open 10-18 every day except Mon. Entrance is free

Info: www.emaproject.eu www.regione.lazio.it