Tiepolo, Venetian fantasies on show in Helsinki

The Rolando and Siv Pieraccini Collection

ROME -- The summer exhibition at Sinebrychoff Art Museum of Helsinki, Finland, is focusing, until September 4, on prints and drawings by famous Venetian masters, the Tiepolos. Rolando and Siv Pieraccini’s unique Tiepolo Collection features works by Giovanni Battista (Giambattista) Tiepolo (1696−1770) as well as his sons Giovanni Domenico (Giandomenico) Tiepolo (1727−1804) and Lorenzo Baldissera Tiepolo (1736−1776).

Giambattista’s works were highly sought after by the royalty and nobility of the day. Together, the father and sons set up a highly prolific workshop, which received commissions from churches and palaces across Europe. The Tiepolos worked for the Spanish royal court between 1762 and 1770, until the death of Giambattista. Some of the works in this exhibition relate to the larger commissions in the Tiepolo oeuvre.

The Tiepolos were also highly skilled printmakers, with Giandomenico and Lorenzo studying the technique, along with drawing, at their father’s studio. This exhibition features some of the best-known prints ever created by the Tiepolos, including the full series of Giambattista’s I Capricci (1741−1742) etchings. Ever present in these prints and sketches are the airy lightness of the Venetian masters’ compositional style and the soaring dynamism of their lines, as well as their playful approach to the fantastical, and the freshness with which they interpret more traditional motifs.

Giovanni Battista (Giambattista) Tiepolo (1696–1770) is widely considered to be the most important painter of the 18th century. In addition to oil paintings, the Venetian master completed numerous wall and ceiling frescoes for churches, palaces and Italian villas. Along with notable buildings in his native Venice, he was also called upon to design decorative finishes for properties further afield, including the royal palace in Madrid. His main work is the extensive series of ceiling frescoes at the Würzburg Residence, which he completed between 1751 and 1753, assisted by his sons Giandomenico and Lorenzo.

In the Tiepolos’ paintings, the more cumbersome Baroque style gives way to a light and bright palette and airy compositions characteristic of the Rococo era. The father and sons’ art also contains references to Venetian opera and theatre of the time.

In addition to large-scale frescoes, Giambattista and his sons Giandomenico and Lorenzo also pursued printmaking, primarily using the technique of etching. Along with the works of Piranesi, the Tiepolo prints count among some of the most highly regarded of their era. Giambattista’s prints are characterised by the soaring dynamism of his lines, his fresh and inventive approach to composition and his steadfast commitment to allowing empty, unused space to remain, which lend the prints the same sense of airiness present in his paintings.

In his printmaking, Giambattista focused on pastoral and urban scenes, with a particular preoccupation with small-scale fantastical subjects, such as those seen in the Scherzi di Fantasia and I Capricci series. The Pieraccini collection comprises the complete I Capricci, a series of explorations on human caprice. According to the 1986 catalogue completed by Dario Succi, Giambattista’s print oeuvre comprises a total of 80 etchings.

Giovanni Domenico (Giandomenico) Tiepolo (1727−1804) served as his father’s assistant on many of his larger commissions, including Würzburg and Madrid. Following the death of his father in Madrid in 1770, Giandomenico returned to Venice. At this point, his paintings begin to eschew the mythological and celestial visions of old, moving towards a more realistic and secular form of expression. Giandomenico completed a number of portraits of notable Venetian figures, representing their life stories on canvas. He also depicted characters from the commedia dell’arte, including Pulcinella.

Like his father, Giandomenico had an interest in etching. His graphic art output is even more extensive than Giambattista’s, encompassing a total of 182 works (Succi, 1988). His lines are more systematically applied than his father’s and, though his works lack the dynamism so characteristic of his father’s, the neat groups of lines form rhythmical textures and shades that imbue them with a delightful liveliness.

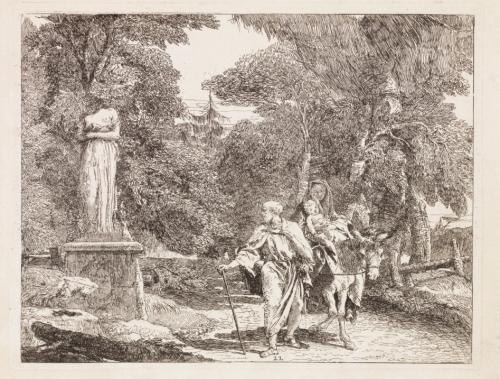

Many of Giandomenico’s prints are reproductions of frescoes painted either by himself or his father. He also produced a number of etching series, such as the Flight to Egypt, comprising 24 prints and the Raccolta di Teste (1774), a study of old Venetian men, comprising a total of 60 portraits. Giandomenico also completed a number of ink and wash drawings. The Pieraccini collection includes one such work by him and a further one by his father, Giambattista.

Lorenzo Baldissera Tiepolo (1736−1776)

Giambattista’s younger son, Lorenzo Tiepolo, also assisted his father on his larger commissions, including the decorations created for the Würzburg Residence and the royal palace in Madrid. Following his father’s death, Lorenzo chose to remain in Spain for the remainder of his own life, working as an artist in the court of Charles III of Spain. He completed numerous highly accomplished pastels of the courtiers and other upper class Madridians. In addition to the portraits, he also recorded everyday Spanish life using the same technique.

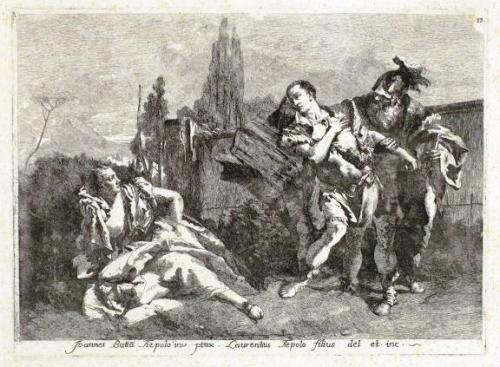

Lorenzo’s print oeuvre comprises just ten etchings, five of which are found in the Pieraccini collection. All ten are carefully executed copies of Giambattista’s paintings. Three of these depict the story of Rinaldo and Armida from Torquato Tasso’s hugely popular Jerusalem Delivered, which also inspired a number of operas.

In keeping with the Counter-Reformation spirit of the time, the remainder of his etchings depict religious topics or large-scale scenes from the Tiepolo ceiling frescoes. Unlike his father, Lorenzo sought to avoid empty, unmarked spaces. Instead, his etchings consist of dense, systematically realised series of lines, executed in varying rhythms.

Handmade paper

Until the 1750s, paper was made by hand. It is only after the mid-18th century that industrial processes begin to proliferate. The process of paper-making was a specialist craft in its own right, mostly carried out in small workshops.

Traditionally, paper was made from cotton and linen rags that were cut and ground into a fine, fibrous mass. When water was added, it created a thick slurry that was then poured into a mould. The mould was designed to allow the excess water to drain away, after which the porous sheet of paper was placed in a press that eliminated any remaining water. After drying, the paper was ready for use.

The mould consists of a wooden frame mounted with a mesh backing wire. If you hold a sheet of manually produced paper against the light, you will see thicker, more widely spaced threads running in a single direction. These are not unlike the warps used for weaving cloth. The thinner, more densely laid wires running at right angles to the warps, are the wefts.

Thanks to its neutral pH level, paper made from rags keeps for longer periods, unlike, for example, the more acidic, wood pulp newspaper, which yellows and becomes extremely brittle over time.

Watermarks

Old handmade sheets of paper usually feature a watermark, an impression introduced during the production process. The watermark is a wire pattern attached to the mould. Watermarks are often shaped like a lily, a crown or a half-moon.

The watermark and the wires forming the backing on the mould leave the paper thinner where they are located and, viewed against the light, are visible as lighter lines and a lighter pattern on the sheet. There are a number of highly comprehensive printed catalogues available that list all the different watermark designs, and these can be used to trace the origin of a sheet of paper. The watermark reveals the earliest possible year the paper could have been made. As larger sheets were commonly cut into smaller pieces for printing purposes, the watermarks are only included in some of the works.

The most important watermark catalogue is Charles-Moise Briquet’s Les filigranes. Dictionnaire historique des marques du papier dès leur apparition vers 1282 jusqu'en 1600 avec 39 figures dans le texte et 16 112 fac-similés de filigranes, Geneve 1907. It contains catalogue entries and facsimiles of more than 16,000 European watermarks and their makers.

For additional information please see below:

Opening hours: Tuesdays, Thursdays, Fridays 11:00‒18:00 | Wednesdays 11:00‒20:00 | Saturdays, Sundays 10:00‒17:00 | Closed on Mondays

Bulevardi 40, 00120 Helsinki, tel: +358 (0)294 500 460,

How to get there: tram line 6, busses 14, 17, 18 and 20.

ch-gn