Pasolini’s Ashes: A night on Palmiro Togliatti Avenue

PIGNETO – While students are chatting over a beer in bar Necci, down the road, tourists gaze at a mural of a stern looking man. In the main street, in the Vecchia Cantina, aluminium wine barrels carry black-and-white photographs of a movie director and his assistant. The Pigneto is selling Pasolini by the pound. All credit cards accepted.

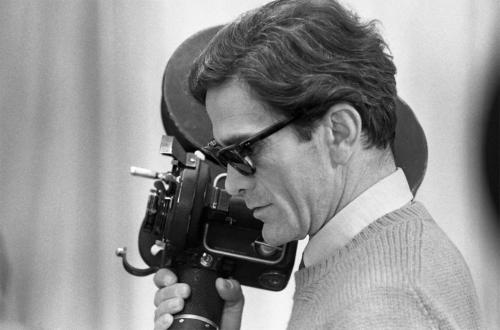

Pier Paolo Pasolini shot his debut movie, “Accattone”, here in the 60ies. Yet, I cannot find any of the shacks or their inhabitants, internal migrants who had been expelled from Rome’s historic centre. Has Pasolini’s prophecy on consumer society finally materialised? Where are the ragazzi di vita? The Eternal City has swallowed “this part of Rome that was not Rome.” I had better leave the centre and head off to the boroughs.

On Via Prenestina, tram 14 takes me through what once was the Giordani slum. In Pasolini’s time, the slum opened to “a prairie where one can see the periphery with its boroughs.” Now, boutiques and shoe stores, bank offices and real estate agencies, “gelaterias” and cafeterias alternate endlessly.

When the double wall of apartment buildings transitions into a series of service stations, and just before the rail track turns right, the tram halts on a vast crossroad. A field opens out on the left. A street sign reads “Viale Palmiro Togliatti.” I alight.

The field makes part of the wedge of “Agro Romano”, Roman countryside that cuts the city right into Tiburtina station.

I cross the road and enter the field. Most of the grass is scorched. Between sparse trees mounts a pile of clothes someone has gone through. I follow a dusty path. After a while, a group of girls is walking in front of me. They are wearing long skirts and are pushing empty prams.

Iron fences to our right mark private property. A billboard shouts “Il mattone: ancora il migliore investimento!” From behind the hill on our left sounds heavy drilling. Cranes pop up between a hotel, a shopping mall and unfinished blocks of flats.

The girls turn in Via Salviati. Below a railway bridge, the leaking sewage has created a large pool we have to wade through. After the bridge appears a grey, miserable slum. A gypsy camp. Two actually: Bosnians and Montenegrins live on one side; Serbs on the other. One-third of Rome’s gypsy population lives in this municipality.

Numerous vans stand parked with their back doors open. Children are unloading used furniture, broken household devices and scrap metal.

A dark column of smoke rises high up in the sky. The gypsies are burning car tyres. Car dealers, who are obliged to recuperate used tyres, pay the gypsies to burn these tyres.

The residents of the brand new compound facing the gypsy camp protest regularly against the fires –burning gummy releases pure dioxin. Since developers elected the East of Rome for shopping malls, the authorities have been razing the camps, pushing their inhabitants outside, beyond the ring road.

I stroll back to the crossroad. From behind a hill looms a long, serpentine block of flats. The building, a council estate, dates from 1979. Its first tenants had been dislodged from the Pietralata and Quadraro boroughs. Originally, the council estate was to house a shopping mall and cultural and local organisations. But all these commercial spaces remained empty. Tenants now sublet them to immigrants.

Last November, the neighbourhood protested against the opening of a second refugee centre in the area. Three days in a row, the council estate tenants set alight storage containers, swirled Molotov cocktails at police officers and sent a bomb letter to the local police station. A poor men’s war had broken out: the Third World was opposing the Fourth World; first-generation immigrants were clashing with third-generation immigrants.

At the other side of Via Prenestina lies the Alessandrino neighbourhood. It comprises two boroughs: the Quarticciolo and the Alessandrino.

The Quarticciolo borough dates from the Mussolini era. When the fascists embellished Rome, they expelled the lower classes from the centre to new-built boroughs called borgate. The Quarticcioli residents were artisans who originally came from Puglia -many street names evoke the region. Cut off from their clientele in the centre, the artisans would become Rome’s “cintura rossa”, the builders that built the modern city.

“And dust, far from the city/And far from the country/jammed each day/in a rattletrap bus/and every trip, every return/was a Calvary of sweat and nerves.” Whereas Rome’s borgate stood isolated in the countryside, they now make part of the periphery. Yet, the borgate’s geometry of plan and harmony of style distinguish them from the rest of the suburb: they are identifiable cells in anonymous plasma.

In 1969, while Rome’s overall unemployment rate was 6.2%, in the borgate it was up to 15%. And while Rome’s average per capita income was 964,000 lire; in the borgate it was between 550,000 and 850,000 lire. Four decades later, the Quarticciolo’s unemployment rate doubles that of Rome’s. Entrepreneurs and liberal professions account for only 11,3% of its residents.

One-third of Rome’s population lives in the former borgate, now officially called “quadranti urbani privi di funzioni pregiate.” Soon, the new Underground line will turn the Quarticciolo from periphery into city. When the council housing entity will privatise these apartments, artists and hipsters will discover the neighbourhood. They will boost rents and push the original residents towards the orbital road.

I continue towards the Alessandrino borough. An impressive aqueduct spans the avenue. Below the arcs, I meet Morgana, a 6-feet tall mulatto transsexual.

Morgana is 26 and from Recife, Brazil. She offers me a coconut sweet from her home country. We have a chat. She fires off one cracking joke after the other revealing that she has picked up the typical Roman lingo and humour.

What this contemporary ragazzo di vita does not tell me is that most of the money she makes on the streets of Rome goes to a slum landlord who sublets her a basement apartment, an annexe or shed in the garden she has to share with other illegal immigrants.

Across the avenue, several men get off the bus. They are wearing tunics and hats. As they proceed through the streets behind the aqueduct, more men join them. They become a whole crowd! Ever more shops carry Arab signs. The men enter a garage in front of which two men take guard. Blankets are spread out on the concrete floor. There is a place for people to wash their feet. In the capital of Catholicism, whose 900 churches stand empty, a mosque with more than 2,000 faithful operates in an ordinary garage!

Back on Palmiro Togliatti Avenue, at the terminus of tram 14, two groups of men are waiting in the cold. These Romanian and Albanian plumbers, carpenters, electricians, masons etc. have replaced the “cintura rossa”. At the crack of dawn, these builders alternate with their female compatriots who have been walking the street at night. Middlemen in vans will replace punters in cars. The middlemen will pick some of the builders and take them to the building sites.

I jump on the bus. A gypsy girl is accompanying her little brother. They are sweaty; their skin is full of sores. Nobody wants to sit next to them.

The children get off at the crossing with Via Casilina. So do I.

“Figli di uno stesso padre” says a large sign on an abandoned service-station. To the right extends a vast prairie. In the Sixties, gypsies installed themselves in a camp that had been built by migrants from Naples. A decade later, the area hosted 2 adjoining camps: Casilino 900 and Casilino 700, the latter being Europe’s largest gypsy camp. In 2010, the city council razed both camps and moved their inhabitants to the state-built camp in Via Salviati and another one near the orbital road which then became the largest gypsy camp in Europe. Five years later, several members of the former city council are in prison. Police interceptions recorded one of them saying: “Do you know how much money [lodging] immigrants and gypsies yields? Even trafficking drugs is less profitable.”

A wall of car wrecks -a graveyard of consumption society- hides the former camps from the avenue. Further down the avenue, a dome pops up. It is the San Giovanni Bosco basilica. Pasolini used this massive church in “Mamma Roma”. The church is empty.

A couple of streets off Palmiro Togliatti Avenue rises the boomerang-shaped council housing estate Mamma Roma hoped would give her a decent reputation and her son a better future. When the Muratori estate was finished, the authorities installed 15,000 people in a near desert. The quarter supplied workforce and figurants to the nearby Cinecittà studios.

The view certainly has changed from Mamma Roma’s: the once solitary building now stands crammed between anonymous apartment buildings and instead of aqueducts and prairie there are shops and parked cars.

Hardly anybody in the quarter remembers its name: Cecafumo, named after the fires shepherds released in the fields.

Back on Palmiro Togliatti Avenue, I pass the Cinecittà shopping mall and its parking lot that is stacked with shining cars. At the end of the avenue, I turn left. Soon I stand before the entrance of Cinecittà. Pasolini wrote scripts in Italy’s Dream Factory before he turned his back to the studios and took his camera to the streets.

I walk along the high wall that hides the legendary film studios. Cars are rushing by. The Cinecittà Underground station is the line’s one-but-last. Cypresses and ruins mark the horizon –the Agro Romano.

Behind the parking lot in Via Giulio Eudo opens a field. A hole in the iron fence leads to an improvised path. Almost invisible, as if hidden, stands a concrete cube. The inside of the cube is a pit. An improvised staircase leads to the old Cinecittà sewage system that now is in disuse. Behind the cube, between burnt rubbish, a man is repairing an old bicycle.

Romanian immigrants live inside the system’s dark and rat-infested tunnels. Because there is only one entry, any fire turns the complex into a mice trap. How long have these people been living here? How long will they be able to stay?

Barely 10 metres from the cube is a dog park. An Italian woman, wearing sweatpants, a baseball hat and sunglasses, opens the gate, enters and unleashes her two small pedigree dogs.

Behind the dog park, an almost unused road separates the field from the countryside. At the other side of the road, brand new, shining office buildings stand empty.