Satires of love or hate: Jonah to Charlie Hebdo

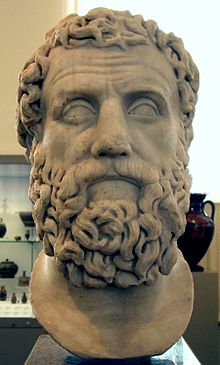

PERTH -Death and satire are no strangers- As early as the 7th century BC Archilochus’ satire was thought demonic with power to kill its intended target.

Satire was then believed to have magical powers not dissimilar from ancient curses that were thought to be deadly. As the belief in magic and curses waned the satirist was no longer perceived to have supernatural powers.[1] Yet, satire was still believed to be injurious to its victim. For instance, there are two reported cases where Muhammad, who tended to avoid unnecessary bloodshed, executed popular female satirists. King Saul’s demise was signalled by the humiliating songs of the ‘dancing women’. Barak of the Bible story, only agreed to go to war against Sisera if Deborah, a well-known satirist would accompany him. Her satirical musings were known to rouse the otherwise apathetic tribes of Israel.[2]The language we use to speak of satire today (venomous, caustic, cutting) preserves the dangerous origins of this form of discourse.[3]

The potential danger of satire should be known to any satirist who is well versed in the craft. It was certainly known to the satirists of Charlie Hebdo, whose offices were fire-bombed after they published a controversial cartoon depicting the prophet Muhammad, on the cover of the magazine. However, Charlie Hebdo persisted with their satirical attack regardless of the negative consequences. It is difficult to suggest what their motivation was for doing so. Indeed, Freud has even warned us to be suspicious of our own intentions, which may not be consciously known to us.[4] Thereby, although Charlie Hebdo waved the banner of the right to offend all people equally, other possible motivations, such as celebrity, and rebelliousness must also be considered. Stephen Post’s suggestion that the anti-religious nature of the French Revolution is still embedded in France may be another helpful avenue for understanding the motives of Charlie Hebdo.[5] Of greater interest to this discussion, however, is the discernment of the type of satirists these cartoonists were.

Gilbert Highet suggests that there are two types of satirists; the optimist and the pessimist. He argues that the optimist likes people and hopes to cure them of their vices. The optimist uses frank and obscene words, however, does so in order to shock people into facing the truth. The primary function of this kind of satire is reform. On the other hand, Highet argues that the pessimist hates people, as he or she finds them to be incurably evil and foolish. The pessimist, thereby, does not hope for the restoration of the world, but conversely hopes to destroy the world through cruel words.[6] I would suggest that Highet’s description of the pessimist is too strong. A pessimist is more aptly described as a person without hope. Such people sense that they cannot offer a workable solution to a social or political problem. I would then argue that the cartoons in Charlie Hebdo were closer to the destructive, pessimistic style of satire. This will become evident in the comparison with the Book of Jonah that is a satire concerning a similar political difficulty.

The Book of Jonah meets the criteria of satire, which includes: grotesqueries, distortions, ridicule, rhetorical features, and irony.[7] Moreover, the narrative of Jonah shares another striking feature with the recent cartoons in Charlie Hebdo. It is a polemic against the Assyrians of Nineveh (present day Iraq), who were spoken of as being violent and immoral. At the core of this story is the hapless prophet Jonah. He is commissioned by God to preach against the atrocities committed in Nineveh. Jonah famously runs in the other direction. A chain of fantastic events bring him to Nineveh, nonetheless. There his mission is a success, as the Ninevites change their ways and turn their hearts and behaviour from violence. However, the instant transformation of these violent terrorists is not the greatest surprise, nor the climax of the book of Jonah. Instead, the reader is shocked by Jonah’s admission that he fled from God’s call, not because of fear, but rather because he knew God would be merciful to the Ninevites. Jonah wished for vengeance, despite the peaceful outcome in the story. However, regardless of Jonah’s anger the message of this story is a clear narrative of hope. God’s abounding and unconditional love can overcome the scourge of evil, where retributive justice and combativeness fails. This message takes away the edge or the danger of satire. This satire is plainly optimistic, as can be observed by the English translation of Jonah’s name (“faithless one”).

On the other hand, Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons are nihilistic. This destructiveness is best observed in the casual manner in which Muhammad is depicted contrary to Islamic standards of blasphemy. Representations of Muhammadnot only provoke extremists who are certain to respond with violence, but also victimise mainstream Muslims. By offending moderate Muslims Charlie Hebdo exhibited the cruelty of the pessimistic satirist. Moreover, they alienated the community with the best chance of finding a solution to the problem at hand.[8] The severity of this cartoon attack is a plain provocation. Charlie Hebdo provided its readers with outrage but did not offer a constructive outlet for this intense energy. From this perspective, the Pope’s recent comment that a provocation may be met with a ‘punch’ is correct. To enrage a person without offering a non-violent solution is reprehensible. The likely outcome in this instance is violence. The truth of this claim, sadly, is evidenced in the recent carnage in France. It may even be suggested that these cartoons proved to be nihilistic and self-destructive.

The legal argument for the freedom of speech is complex. It is not the intention of this article to enter this discussion directly, nor to suggest legal boundaries for the freedom of speech and expression. I suggest it is more profitable to focus our attention on the constructive and destructive outcomes of satire. In doing so, we are aware of our freedom to speak and otherwise express ourselves with the view to positive solutions, or with foreseeable violent results. Yet, the choices we make point to our intelligence, psychological health, and civility. The optimistic satire in the book of Jonah offers us a message of love. It is powerful and constructive. The pessimistic cartoons of Charlie Hebdo deliver the destructive force of hate. Whether or not we personally accept the message of the book of Jonah, or the destructiveness of Charlie Hebdo is a matter of individual choice. However, pessimistic satire is limited; it cannot offer us a solution. On the other hand, the function of optimistic satire is reform. The book of Jonah offers us a solution to extremist violence by encouraged reform in our god understanding. To demonstrate this point, the interface of theology and psychology needs to be invoked.

Psychology can offer perspectives which heal or conversely damage a human being. The only psychologically healing image of God, is the God of unconditional, universal, and radical love; the Jonah message. If we refuse to see this we must cling to the outmoded and dangerous conception of a god who is preoccupied with defensive-aggressiveness, vengeance, and retaliatory justice. This is the position of the religious extremist. If this is the choice we make, we resign ourselves to a life of fear and anxiety, as violence is demonstrably harmful to human beings. This belief structure cannot bring forth a feeling of peace, but only apprehension of the next violent encounter.[9] If like Jonah, we are overtaken by a desire for vengeance, despite the clear evidence that it is love which heals and not violence, then we may be considered irrational and pathological. We are similarly so, if our stance is an extremist anti-religious one as Charlie Hebdo appeared to be. It is extremist in so far as it refuses to comply with even minimum standards of respect for what religion holds sacred.

Of course, a frank critique of religion is necessary, as the Book of Jonah suggests. However, this is only constructive if it is balanced with a sensitivity toward what is held by the religious to be sacred and an openness to the possibility that there are positive features and outcomes of religion. At present the positive outcomes are evident in the decision of faith leaders to unite in opposition to extremism, and to alleviate suffering. Consider this statement from Bishop David Murray of Perth Australia:

Since our visit to Cairo a few years ago, the Anglican Bishop in Cairo now holds regular meetings with the leaders of the other churches and also Muslim leaders. There have been some beautiful exchanges of mutual love. It could be that the single mindedness of any fundamentalist groups (Islamic, Christian, or Jewish) will drive the moderates together and therein lies the power of unity in The Spirit.

He also went on to speak of the work of the Global Freedom Network for the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Pope, which now includes leaders of all faiths, who have come together, for example, to eliminate slavery by the year 2020.[10]

“We are not Charlie,” in as much, as we are not pessimistic satirists who have been annihilated by the dangers of satire, and provocation. Yet, this is no reason to abandon the recent catchphrase Je suis Charlie. The press has touted this expression as a protest in favour of freedom of speech, yet, this is not the case. Millions of people across the world are not claiming the right to be blasphemous, nihilistic and destructive satirists. If this were the case, the magazine Charlie Hebdo would have had a stronger readership prior to the assault on their offices. Plainly, this style of satire is not, ordinarily, that popular, because people are naturally more hopeful, and inclined to positive solutions. In this instance, when people speak of freedom of speech, they are arguing for the freedom to express dismay at the injustices of the world.

Moreover, we want to put an end to these injustices. Freedom requires and wishes for responsible action. The scenes of unity, hand-holding and the outpouring of love we encountered after the recent events in Paris are the real meaning of Je suis Charlie.

It is an expression of transforming unity and love. The argument for an alleged moral right to speak with inflaming hatred appears contrary to this display of support. “Love never fails” (1 Cor. 13:8).

Virginia Ingram is a lecturer of academic language and literacy at Murdoch University in Perth, Australia. She is the author of Grace: Free, costly, or cheap?

Footnotes:

[1]Robert C. Elliot. The Power of Satire. (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1972), 4-6.

2S. D. Goitein. Jews and Arabs. Their Contacts Through the Ages. (New York: Schocken Books, 1964), 30.

3Robert C. Elliot. The Power of Satire. 4.

4Paul Ricoeur. Freud and Philosophy. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970), 32-33.

5Stephen G. Post. Hope in Paris – An Open Letter to Charlie Hebdo (New York: The Institute for Research on Unlimited Love, 2015. Last modified January 26, 2015). http://www.unlimitedloveinstitute.org

6Gilbert Highet. The Anatomy of Satire. 21.

7David Marcus. From Balaam to Jonah. Anti-prophetic Satire in the Hebrew Bible. (Georgia: Scholars Press, 1995), 9-28.

8Stephen G. Post. Hope in Paris – An Open Letter to Charlie Hebdo.

9J. Harold Ellens. Radical Grace. How Belief in a Benevolent God Benefits our Health. (London: Praeger Publishers, 2007). 1-10

10Bishop David Murray. Email Correspondence (January 18, 2015