Whistleblower exposes Vatican Bank shenanigans

Rome—When John Paul II became pope in 1978 he inherited a number of relationships that would later prove embarrassing for the Vatican. Entanglement with dubious financiers such as Michele Sindona and Roberto Calvi, would bring lasting discredit on the Catholic Church.

The choice of such disreputable business partners – both had links to the mafia and were involved in ruinous bankruptcies – may have seemed justified at the time by the requirements of a clandestine global struggle against atheist communism. Both men were staunch anti-communists and members of Licio Gelli’s right-wing masonic lodge, P2.

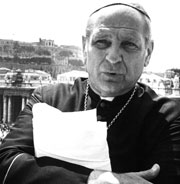

Some 30 years on, the memory of the financial scandals associated with the name of Paul Marcinkus, the Lithuanian-American archbishop who ran the Institute for the Works of Religion, the Vatican bank also known by its Italian acronym IOR, is beginning to fade.

We were led to believe that a new broom, wielded by the lay banker Angelo Caloia, had since swept clean the premises of the IOR, housed in the medieval Bastion of Nicholas V. The Vatican, it was thought, had learned the painful lessons of the Marcinkus era.

That assumption has been called into question by a new book, “Vaticano SpA” (Vatican Ltd), written by the Panorama reporter Gianluigi Nuzzi. A cavalier attitude to financial ethics continued well into the 1990s, with huge political bribes being laundered through the IOR and funds donated for charitable purposes being casually misappropriated by the bank’s administrators, according to Mr Nuzzi’s reconstruction.

Mr Nuzzi’s allegations are based on internal IOR documents, more than 4,000 in all, that were smuggled out of the Vatican by a disgruntled employee. This unique violation of IOR confidentiality was made possible by an unlikely whistleblower: Monsignor Renato Dardozzi. An electronic engineer who held a top job at the state telecommunications company, Mgr Dardozzi was ordained priest at the age of 52. He worked in the IOR under Marcinkus, participated in the joint Vatican/Italian commission that examined the IOR’s role in the collapse of Mr Calvi’s Banco Ambrosiano, and witnessed Mr Caloia’s uphill struggle against the personnel and practices of the Marcinkus era.

The chief exponent of the old guard appears to have been Monsignor Donato De Bonis, who served as secretary general under Marcinkus and perpetuated the latter’s administrative legerdemain under the new regime.

In 1987, according to Mr Nuzzi, Mgr De Bonis set up the Cardinal Francis Spellman Foundation, with its own account at the IOR. Signatories on the account were De Bonis himself and Giulio Andreotti, the veteran Christian Democrat politician. During its first six years of operation the account received some 50 billion lire (€26 million) and paid out 43 billion.

Though Dardozzi’s documents show that Andreotti and De Bonis were beneficiaries of the Spellman account, the internal IOR correspondence is coy of admitting as much. The Christian Democrat politician is often referred to cryptically as Omissis, while De Bonis goes under the codename Roma. Ownership of the account was clearly a sensitive matter.

The choice of the virulently anti-communist Spellman as “patron” of the fund is interesting. The well-connected cardinal of New York earned the sobriquet “money-bags” for his fund-raising skills and he earmarked significant sums for Italy’s Christian Democrat Party during the cold war years.

The Spellman fund seems to have been administered by De Bonis with promiscuous generosity. A variety of convents and clerics were to benefit, with payments ranging from the modest 1 million lire paid to five mother superiors, to the $50,000 sent to the auxiliary bishop of Skopje-Prizen, for the Albanian-speaking faithful, and the $1 million delivered to Cardinal Lucas Moreira Neves, the archbishop of Sao Salvador de Bahia in Brazil.

There were also payments of a more personal nature: 100 million lire for one of Andreotti’s lawyers, $134,000 for a New York conference on Cicero sponsored by the former prime minister, and even a 60 million lire payment to Severino Citaristi, a former treasurer of the Christian Democrat Party convicted of corruption.

In 1991 the account paid some 54 million lire in six instalments to Gioconda Crivelli, a jewelry and fashion designer who appears to have been a personal friend of Mr Andreotti. And a 5 million lire payment went at the same time to Monsignor Giuseppe Generali, described in an interview by Andreotti’s political colleague Walter Montini as Andreotti’s “spiritual guide”. “He was so close to Andreotti as to become the protector of his sons during the dark years of terrorism,” Montini said. How a churchman could perform such a function was not explained.

Part of the massive Enimont bribe, paid to politicians to secure their approval for a reorganisation of the chemicals sector, was also bounced through the Spellman fund, according to Mr Nuzzi. But Mr Caloia and Mgr Dardozzi chose discretion over transparency when questioned about it by prosecutors from Milan. “Despite the full collaboration promised and publicised in the press, they limit themselves to referring only what can no longer be concealed,” Mr Nuzzi writes.

Mgr Dardozzi’s documents reveal how the IOR leadership debated how much it was safe to reveal to the prosecutors. In a note to the cardinals’ oversight committee, Mr Caloia warned of the sensitivity of the issue. “Any leak would constitute a source of grave harm for the Holy See,” he wrote. “And that because the document outlines procedures and figures that – not being essential for the Milan prosecutor’s office – have not been transmitted.” The reserve was motivated, Dardozzi observed wryly in a note to the IOR’s chief lawyer, by the need to avoid “leading (the investigators) into temptation”.

It is interesting to note that Mgr Dardozzi’s motive for turning whistleblower was not unalloyed disapproval of the IOR’s unethical conduct. His decision to smuggle his secret archive out of the Vatican sprang from anger at the institute’s refusal to pay him a commission on the sale of a valuable villa near Florence. The unusual monsignor wanted to leave the money to his adoptive daughter, whose health condition required expensive hospital treatment.

Whatever the reason, Dardozzi’s archive offers an unprecedented glimpse of the inner workings of one of the world’s most secretive and unaccountable financial institutions. The idea that a noble end – winning the cold war or funding one’s favourite charity – justifies almost any means, still seems to endure at the pope’s bank in the Nicholas V Tower.

The topic of the Vatican bank’s financial shenanigans continues to fascinate the Italian public. Despite negligible publicity in the press and on television, “Vaticano SpA” jumped to third place in the non-fiction rankings within 10 days of publication.http://blog.panorama.it/italia/2009/05/17/ior-parallelo-conti-segreti-in-vaticano/. )