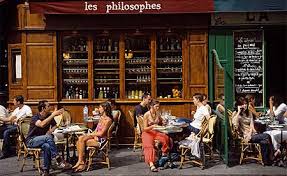

The existential burger

PARIS--Ask the average American to discuss his philosophy and he’s likely to declare that he believes in rotating his tires every 10,000 miles.

Ask almost any Frenchman to discuss tire rotation and he’s apt to produce a disquisition on cosmic verities, delivered in neat syllogisms complete with verbatim quotes from Descartes, Voltaire, Derrida and Sartre. The Gallic conclusion seems to be that although Americans may cruise down the rough road of life with plenty of rubber between the potholes and their rumps, they haven’t the foggiest idea of the metaphysical implications of their journey.

What the French refuse to recognize are the historical roots of the American tendency to be impatient with abstractions. Because we had a frontier to conquer, we became a can-do people. By contrast, the French are a do-Kant people who sometimes give the impression that it’s just as important to ponder a problem as to solve it.

Even in the arena of amour, a topic on which they are reputed to possess great expertise, they’re inclined to fall back on philosophy, and when pushed to define the nature of love, they quote a pensée from Pascal who wrote that “the heart has its reasons that reason cannot know.” Not the heart has its mysterious urges, desires or emotions. No, for them, the heart, like the head, is a hive of ideas to be dissected and discussed.

I remember an afternoon 10 years ago when the French Countess de Breteuil, in the course of showing me her villa in Marrakech, seized every opportunity to demonstrate the philosophical sinuosity of her mind and the crude circuitry of my own. As we passed through a courtyard swarmed over by turtles, I expressed surprise and incomprehension. Why were the cobblestones crawling with turtles? The Countess arched one all-knowing eyebrow and cryptically commented, “Because turtles are so amusing.”

After we had climbed a tower at the edge of her property, she observed when we trudged down the circular staircase, “As in life it is always easier to descend than to rise.”

How do they do it? I marveled. How do the French manage to dispense pithy aphorisms on every topic from reptiles to social mobility? The Countess explained that it comes down to education. Starting in high school, French students are required to take philosophy for eight hours a week. While our level-headed little ones are off at Driver’s Ed or Sex Ed seminars, dutiful Gallic adolescents are thinking and, more importantly, thinking in the French fashion. On the baccalaureate examination, taken by half a million teen-agers annually, they kick around questions that are as interesting to them as whether Elvis still lives is to us. To savor a couple of sample Bac brain teasers, sink your teeth into these: “Does knowledge inhibit the imagination?” “Is a coherent thought necessarily true?”

While I’ll concede that a certain amount of navel gazing and cud chewing can be every bit as amusing as a courtyard full of turtles, I know that France’s philosophical bent causes trouble for travelers from different cultures who arrive with the delusion that they’re on a holiday. They’re actually sitting for a secret examination and they’ll be graded for every word, every concept they utter. Failure produces not just ego damage, but also the real risk of not finding the right road, a room in a hotel or a meal in what they imagined to be a restaurant. Twenty-nine years ago when I was a Fulbright newly arrived in Paris, my formative encounter occurred in a laundry when I asked if I could have my shirts washed without starch.

“Monsieur,” said the owner, “we will do the necessary.”

Fetching about for le mot juste, I tried to convince him that the necessary wasn’t what I needed. Starch gives me a rash.

But the man stuck to his first postulate, repeating like an existential sage that as between being and nothingness he could only do the necessary. I decided to wash my shirts in the kitchen sink.

Just last summer I made the mistake of asking French friends about dropping off a rental car. Should I leave it at the airport or drive it to Paris?

This provoked hours of Hegelian wrangling that ultimately involved their daughter, some neighbors and visiting relatives, who proposed various theses, antitheses and syntheses. Each insisted on establishing a major premise, a minor premise and a conclusion. They dithered over timetables, the opening and closing hours of airports, traffic patterns on national highways, and the possibility of carsickness on tortuous secondary roads. Like medieval theologians debating how many angels can dance on a pinhead, they might have maundered on ad infinitum if the family dog hadn’t been stung by a wasp, offering a new subject of speculation. En principe, was the treatment for insect bites the same for animals as for humans? Did dogs process pain as an emotion or strictly as a physical phenomenon?

My son recently returned from a school trip where he stayed with a French family ruled over by a philosopher-king father whose idea of dinner table chat resembled ontological discourse. Asked to recommend a restaurant, the man launched into a long history of food, its symbolism, its central place in French culture. No closer to naming a restaurant, he concluded by reducing the issue to three subcategories—Freshness, Preparation and Presentation. My son roused himself to ask whether the man taught structuralism at the Sorbonne. “Mais pas du tout,” the philosopher king replied. “I am a retired textile salesman.”

The penchant for rumination cannot be separated from the key role of language and to speak French incorrectly is to be perceived as someone who thinks incorrectly and is therefore impossible to understand. I once found myself marooned at the Nice train station, eating lunch at a fast food franchise called Flunch. The place looked harmless enough—it looked, in fact, like a replica of a McDonald’s, right down to a menu that featured fries, shakes and a choice of Burger Simple, Burger Fromage, Burger Big Thesis, antithesis, synthesis.

“Big Burger, s’il vous plaît,” I said.

“Ça n’existe pas.”

I pointed to the menu, which showed a photograph of a cheeseburger with bacon, lettuce and tomato on a sesame bun.

“Ah,” she said, “you mean Burger Big. In French the adjective comes after the noun. You should learn our language.”

“It’s my language. ‘Burger’ and ‘big’ are English words.”

“As you wish,” she said icily.

“What I wish is a Big Burger.”

But I was deceiving myself. What I wished was to convince the woman that although we Americans may lack a certain intellectual sophistication we are not without hard-won wisdom. We have our own homespun equivalent of the three-part Hegelian dialectic, and it serves us just fine: Never eat in a restaurant called Mom’s. Never play cards with a guy named Doc. And never ask a Frenchman any question that can’t be answered by Yes or No.