Revisiting Hemingway's Fiesta!

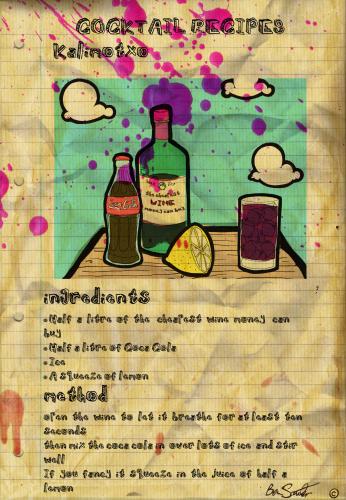

PAMPLONA -- The streets to the bullring are a mess of broken bottles and containers with the remnants of cheap sangria and kalimotxo (a mix of Coca Cola and red wine popular in the Basque country).

The cobbled roads are still thick and alive with thousands of red-and-white-clad revellers, and now the air hangs with a nervous energy after the violent torrent of the bullrun that gripped the OldTown. No one has been killed, but there were several gored and in need of medical attention. Sirens. Shouting. It’s only ten past eight and the stones are still cold and wet with morning dew.

Stepping up and into the bullring and it’s a spectacle of itself for a throbbing mass of tens of thousands of the alcohol-fuelled and the wine-stained spills over every step and seat. The red and green of the Basque flag are draped down between the upper and lower tiers of the coliseum, and these encircle a central sandy arena filled with the runners. Anxiety and elation, and a curious quantity of marijuana. The pot smoke has been regular punctuation in the fiesta, wafting occasionally from tightly packed crowds, and Abbi and I stand midway up the steps from one entrance and behind a group of Australians: “did you see that Chinese guy get taken out?” one of them shouts.

A roar erupts from the far side of the grounds and the multitudes leap to their feet, and down in the ring there is an explosion of movement as two young steers are loosed. Their horns are corked and taped, though they are still as tall as men and one ably catches a runner from behind and throws him up into the air and proceeds to grind the man into the ground. Several nearby runners dart over to him and pull the beast back by its horns.

A larger and faster steer runs about the outside, and men - dressed feet-up in sangria-soaked white with red belts and neckerchiefs - run around as close to the animal as possible, hitting at it from behind as they pass. One man runs to the steer’s flank and somersaults over to a rumble of adulation from the twenty-thousand-strong crowd, and another grabs the animal by the horns and holds it down, wrestling with it. One runner catches sight of this and charges over in a fury and throws the man away from the steer.

You see, there is an odd moral code to the proceedings. A crazy ethic in the midst of all the blood and wine, like a final shred of the humane in the blurred and brutish depravity, and quite at odds with the fact these are men goading two young, underdeveloped creatures that are more cow than bull, and clearly panicked. The whites of their eyes show as they run in electric mania.

One man tries to outrun a steer in a straight line. This quickly proves to be a mistake, and he is caught and hit in the back with a fierce horn, and forced into the ground and trampled and a few men attempt to pull the animal away, but this proves harder than they expect and it lasts for about 30 seconds until the felled runner is at last helped to his feet and off, limping to the stands.

Something has happened and a hundred men swarm the other steer – a white and tawny brown creature with black tape running down its forward-facing barbs – and it quickly becomes lost to them and all you can see is the red-white runners that surround it.

With this, the gates of the corrals open and out emerge olive green men with a colossal bull that must weigh over two tons. Oliver Reed once said that soundmen shouldn’t like a good villain, for a villain should have a great silence about him. This creature is calm but its eyes pierce the crowd and the green men barely come up to its chin: it is the “whispering giant”. They corral it with two-metre-long bamboo poles and it treads the sand into the ring. It pauses behind a runner, right horn levelled directly behind the man’s head, and the man turns and sees it and looks forward as if thinking nothing of it, and then darts round again comically before sprinting away. A burst of twangy laughter from the group of Australians in front of us, still revelling in alcohol and weed.

One of the green men legs it over to the thick of the crowd surrounding the swamped steer. He forces his way through and helps the animal free. As the crowd disperses around it, he lifts his long bamboo stick and furiously swings it at anyone still nearby. It connects hard with one man and knocks him down and he backs away fast. The giant bull is led over and brings the two steers back into the corral and all-of-a-sudden the animals are calm and solemn, and the two men and the three bulls walk in procession in a curious juxtaposition of composure after all there has been.

“I am deeply confused,” I say to Abbi as we walk out and back to the hotel. Like many moments in the fiesta, there is a gripping unease as though one is beginning to feel truly human. It is an uncomfortable and raw and heady feeling and the fiesta is fuelled by the instinctive. But we are in a Latin country, after all, surrounded by passionate men and women. They drink from leather botas and they lift them high above their heads so that a thin stream of wine pours down into their mouths. Music is everywhere, and fervent shouting and singing and, curiously, the riff from the White Stripes’ song “Seven Nation Army” is regularly chanted.

So there we were, in the midst of it…

A few days earlier, we’d taken a train from Montparnasse in Paris down to San Sebastian, where we stopped late in the evening at a café by the waterfront for rich Serrano ham, Queso Manchego and pimientos with bread and unlabelled tannic red wine, which we had in the cool, sweet Spanish air. A few hours later we arrived into a Pamplona engulfed in the midnight. Then the streets were quiet, but raw and ready.

The fiesta began with daytime fireworks, of which the Spanish are particularly fond. The aim is not colour and display but a powerful noise which rains down with the wine and sangria onto the thousands upon thousands gathered in the main square, the festivities marked by the launching of the chupinazo rocket into the sky.

The two of us looked both ridiculous and glorious in head-to-toe white with the streaks of red cloth around waist and neck, and there was not a soul in the town who wasn’t so dressed – a bond was formed despite the language barrier. Walking the fifteen minutes from our hotel to the Old Town, we reached a stop light behind a dozen young Spanish men dressed in red and white. “What brings you to Pamplona?” I asked – a joke that was funnier to me than to anyone else, apparently.

To cap the look off, we had a large swinging wineskin, and this Abbi and I filled with two bottles of the cheapest Rioja money can buy, as well as orange juice. It wasn’t “proper” Sangria, hell, it was made with Sunny Delight, but our hearts were in the right place. Not that it would matter; the Spanish aren’t precious about wine. Coke and wine is a favourite (I think I tried that once in England when I was about 14, and strongly suspected it was a crime against Epicurus himself), red wine with ice in it, or juice or really anything one could wish for. Lemonade works quite well. It makes you feel cheap and dirty to concoct such things, but it’s rather wonderful nonetheless.

We fought through packed masses in a café on our way to the main plaza, and had coffee and a very generous cup of sangria each (it was half ten in the morning, after all), and a wall-mounted CRT television showed footage from the bullruns of yesteryear. “Christ,” I said as I saw a clip of a man trampled into the ground by several one-ton bulls, “you wouldn’t get this in Tunbridge Wells.”

In fact, since the relevant authorities started bothering to record such things (the mid-twenties), there have been 15 deaths in the run -- surprisingly few all things considered. The last to perish was in 2009, and the footage is grim, but the inherent dangers are unquestionably a part of the fiesta’s attraction. It is an intangible connection with the animalistic that gives the thing its edge, and this is a hugely important part of the culture. It is a tiny suggestion of the link between the sedentary modern human and the animal he pretends not to be. This is the aforementioned unease -- the realisation of this very fact.

You can make up your own mind whether or not this is a happy awakening: I suspect it is.

At the encierros, most runners are men and, on the first run of the fiesta, the police select only the most Spanish-looking among them, as opposed to the many drunken Aussies and Americans. Besides, the first run is an opportunity for the “gringos” to appreciate how it all works, and to learn the counter-intuitive cardinal rule: if you fall, it is vastly better to stay down.

The first race began at 8 am, a horrid time to be awake. That Sunny D/Red Wine mix had done bad things to us, and added to that we’d really gone native the previous night. We found a dive bar down a tiny street in the Old Town, and once there we knocked back plenty of some sort of booze. I was greeted by a cheering crowd of Spanish youths who spoke just a few words of English (and my Spanish is really not what it could be), and from what I managed to glean, they believed me to be some kind of football-person, and I had my hand vigorously shaken. It’s nice to be mistaken for a football-person, if anything.

Several mojitos. A bottle of sparkling wine. Various other fluids. Before stepping out that night we went into a bar near to our hotel where one could purchase fresh bocadillos for only a couple of euros apiece. We asked for “doused coffee” (we tried this game in England, but asking for “coffee with booze in it” is invariably greeted with bewildered looks – one must settle for requesting “Irish Coffee” – though, as I’m sure you’ll agree, gentle reader, this hasn’t quite the same romance). The gentleman at the bar had no spirits, and so recommended the kalimotxo…

“It’s coke with red wine in it,” he leant in closer to give the thing more gravity.

“Crumbs!” We said, “Go on then.”

And then followed a joke surely lost in translation: “If you do not like it,” he added, with a great solemnity, “you can kill me.”

“Right-oh,” we accepted his challenge.

He lives.

At the run, the bulls and runners were separated from the crowds by a double row of thick fencing, and all along the streets the spectators hung out of windows, and were perched atop lampposts and scaffolds for a better view. Every now and again a break formed in the masses and you could see the scuffle of quick feet dashing by and, even if you couldn’t see the bulls, one knew where they were by the reactions of the crowd; awe and a little fear with every passing beast.

The bulls ran in front of us, chasing a few men and one of the animals turned in sideways and lunged at a runner. A tension again: desperate curiosity and mild terror. The man lunged toward the fence and slipped beneath the low posts just split seconds before the bull collided with the barrier and turned to re-join the herd. It was a thing to behold.

One afternoon, in a bid to truly fit in, we made up our minds to take to the ground and siesta. All about the place, exhausted degenerates (such as ourselves) littered the grounds - some slept on grass verges, others on benches, and a surprising number would simply lie collapsed and supine at the sides of roads and walkways.

We found very pleasant and ornate gardens in which to slumber beneath tall willows and sycamores that moved heartily in a stiff breeze. I often say this, but that sound of wind in the leaves is a true catharsis: it cleanses one’s very soul. We used the leather bota for a pillow and after two hours were ready for the real mayhem of the night.

As the fiesta progressed, more and more English speakers appeared. These were largely American and Australian and I heard just two English accents the entire trip: one a thoroughly dastardly looking chap who was yelling something in the street, and the other a character we dubbed “The Party Girl”. We met her in San Sebastian, sitting in the corner of a bus station café, and she looked up from behind a blue-grey cloud of smoke: “are you here for the fiesta?”

“Yes. Yes we are.” I announced with a little too much English cheer.

She had a husky, cigarette-stained voice, and a tanned face, and her appearance was slightly leathery and it was impossible to judge her age. She had certainly seen the world, though, and undoubtedly within hours of arriving at the fiesta she’d have found an underground dogfighting ring and would be taking shots of Mescal to the eyeball in between rounds of Russian roulette and methamphetamines.

With more English-speakers, the thing had become darker. The passion of the Spanish was now seasoned with the alcohol-fuelled dementia of our colonial brethren. On the first night, one could kick a man square on the Johnson and passionately embrace his girlfriend in front of him and he’d probably buy you a pitcher of Sangria and you’d become lifelong friends. On night two, however, the wrong sort of look could easily catch one a serious bottling to the face, and this added a tautness to the air that hung about and gathered up in clouds between odorous patches of spilled wine and stale urine.

I had become quite practiced with my bota by this stage, and regularly lifted the thing as high as possible and caught at least “some” of the stream of pouring wine. This, I felt, looked quite impressive. In hindsight, it wasn’t. I know this as my clothes were drenched in Rioja.

We had a tapas of garlic prawns, cured meat, salad with astonishingly peppery olive oil and Manchego and, after, bought a Djembe from a street hawker. We bartered with him and eventually had the thing for twenty-five euros and wandered through the night beating out Spanish rhythms on it. As we walked along, revellers would run out in front of us and dance and then skip away into the throngs, and we offered the drum-skin up to others who would tap it joyfully. A fine thing is a drum!

To complete the fiesta, we decided to watch a bullfight. Our hotel’s concierge – a true aficionado – tipped us off to wait outside the ring an hour or so before the fight, and wander around yelling “para comprar!” until someone sold us a pair of tickets. This, he said, was far more frugal than buying from the ticket machines, but our first step was locating the plaza de toros.

You see, we had become lost in the Old Town, and had wandered in a circle for about two hours, each time passing two drunk and elderly Spaniards, and each time enthusiastically crying “ola!” in their direction. They seemed happy, though not particularly compos mentis.

After all this, we were on the verge of abandoning the entire enterprise when we heard a blaze of Spanish music, and saw men clad in bright colours atop tall horses, and the “gigantes” - colossal papier mâché figures. It was the Saint Fermin procession and it sees the 15th century statue of Saint Fermin carried through the OldTownand up to the bullfighting ring. We were saved!

Around the procession the crowds were thickly packed, and men and women danced a “jota” in the street. There were several other smaller parades, each carrying politically charged banners and slogans, and each meeting at the main doors to the plaza de toros. The cathedral bell rang out…

“Paracomprar!” we duly began to shout…

The first tercio, or stage, of the bullfight, begins with a sounded bugle, and the arrival of the bull. The arena is like a Gladiatorial amphitheatre – all stone and vibrant with draped flags.

The bull is gauged for its aggression by the matador and the banderilleros. It goes for the matador, who performs his ballet, avoiding the great beast whilst remaining as much as possible within its “territory”. He watches for its behaviour, and to see how it might act later.

The horseback “picador” trots out, armed with a lance which he plunges into the muscular mound on the back of the bull’s neck, to weaken and bleed the animal. This stains the sand a little. The picador allows the bull to charge at his horse, which is armoured and quite calm throughout the proceedings, and the matador watches the bull to judge the angle at which it charges. As this first stage wears on, the bull becomes focused.

The second tercio features the banderilleros, who stab the bull with “banderillas” – the colourful barbed sticks which are impaled in the bull for the duration of the corrida. The three men alternate between thrusting the banderillas and dodging the bull with wide capes, pirouetting on their heels. The bull becomes weakened and, by the end of this tercio, it wears several of the multi-coloured spears. Constant applause rings out around. Impassioned chants and drumming.

The final round, the tercio de muerte, sees the matador armed with a muleta (his red cape), and here the bullfight truly begins and ends. The matador contorts his whole body, arching back as he brushes his red cape across the sand of the arena and toward the bull. The animal watches this and holds its ground. It is colour-blind and it is the movement of the cape, and not its colour, that attracts it. Indeed, the red is probably just a disguise for all the blood, and one that has become a tradition in its own right.

The matador repositions himself and continues to move the cape, tempting the creature as it shuffles round on the spot, constantly facing the man. The matador moves in, closer to the bull, luring the one-ton beast with the muleta ‘til eventually it lunges for the cloth. The muleta is rotated and the matador turns on point. It must be drawn as close to the matador’s body as possible. As the bull leaps for him, the coloured banderillas bounce up and after every lunge both man and beast hold still: the matador with oozing pride and flair; the bull with oozing blood and quiet dignity.

"In bull-fighting they speak of the terrain of the bull and the terrain of the bull-fighter. As long as a bull-fighter stays in his own terrain he is comparatively safe. Each time he enters into the terrain of the bull he is in great danger. Belmonte, in his best days, worked always in the terrain of the bull. This way he gave the sensation of coming tragedy."

This goes on for some minutes before the matador approaches the stalls and is armed with his sword. Three banderilleros surround the bull as the bullfighter approaches it, sword held back and at the ready before, finally, he plunges it deep between the shoulder blades and into the heart.

After all of this, at least the final coup de grâce is a quick one, for the bull immediately slumps down into the ground.

The matador walks to the centre of the arena and puffs out his chest. He raises his arms and arches his back with his muleta held high above him and the crowd are on their feet. White handkerchiefs held aloft. The fight is over. The bull carcass is dragged away by horses.

On the corrida, I remain undecided, and it was a constant discussion throughout the fiesta. Many we met in Pamplona felt the same, though feel as you might about the animals there is without question an art in it. The matadors are beautiful and poised and their work is a choreographed blood sport. To see it in the flesh, so to speak, is to truly appreciate their finesse, and also to feel very much like an animal oneself.